Let's say you are enamored with Whirlpool's Duet, the country's top-selling front-loaded washing machine. It is one of the more energy-efficient machines using about 227 kilowatt hours of electricity a year, according to a government rating that appears on the yellow Energy Guide sticker affixed to all new appliances. You can find one at Sears or other appliance stores for about $1,400. (Of course, the cost won't end there. Unless you buy a matching Duet dryer at about $900 to sit next to it, your laundry room will look like a squinty-eyed pirate.) The Duet washer would cost about $78 a year to operate compared with $161 a year for Whirlpool's $549 Ultimate Care top-loader, according to a downloadable calculator on the Department of Energy Web site (http://www.energystar.gov/index.cfm?fuseaction=find_a_product). But because the Duet costs so much to buy, the total cost of the front loader over seven years is $1,946, or $269 more than the Whirlpool classic top loader. Guess what? It makes economic sense to buy the more expensive machine. In theory, a dollar today is more valuable than a dollar in seven years. Therefore, you should be willing to pay $318 more for something that saves you $546 over seven years. (You can do this "present value" calculation at http://www.csgnetwork.com/presvalcalc.html). That calculation will be useful anytime you buy a product that promises future savings.Can you spot the howler? Because the upfront cost of Duet comes first, it should have to save you that much more than the cheaper model over the seven years. In other words, because a dollar is "in theory" worth more today, the Net Present Value (NPV) calculation works against the expensive model... but they've presented it as working in its favor. Two seconds of thinking about this showed me it couldn't be right. How could this end up in the "Your Money" section of the New York Times and not be caught? Update: I've been thinking about this a bit more and I just can't figure out what happened to get these paragraphs published in the NYT. Perhaps some radical last minute editing that accidently got rid of other sentences that would have explained it? I doubt it, but what in the world does the fact that "you should be willing to pay $318 more for something that saves you $546 over seven years" have to do with anything in the article? From the math I do, the Duet washer saves you $581 in energy costs over the seven years, but costs $851 more to buy. Where do the $546 and $318 come from? The closer I look the more this just seems like innumeracy on top of economic illiteracy.

Kevin Laws, guest blogging at Due Diligence, has a very perceptive article on what Hollywood needs to do to save itself from digital obsolescence. Basically, don't repeat the mistakes of the RIAA. The whole thing is worth a read, but his recommendations are:

- Work with DivX to incorporate digital rights management in the standard, no matter how imperfect. AACS is the movie industry's equivalent of SDMI, a consortium of entertainment companies creating a proprietary standard for sharing video. AACS is DOA because it is too late, just as SDMI came too late. It was supposedly announced July 14th, but the web site still says "coming soon" and if you have images off, it still says "coming July 14th". Instead, work with DivX. Allow it to continue to support any movie ripped freely, but with an optional simple encryption with a separately provided key tied to a specific device. Users register "allowed" devices with a third party service and when they pay, it automatically downloads and installs keys that allow the device to play any specific video. It is important for the industry that this become part of the already winning DivX and XviD standards, rather than a proprietary solution.

Free copies of the exact same movies will still be available for download because people will rip the DVDs, just like MP3s are available for almost any song downloaded from iTunes. People still download from iTunes, because as a mass market experience it is better. For those that value their time more than a few dollars, it will be the obvious choice. For the students who don't have the money, they wouldn't have shelled out $50 for a season of the Simpsons anyway.

- Release everything. If I can't get the Simpsons legally, I have that much more incentive to learn how to use illegal file-sharing services. Rather than staging things individually, just make the entire catalog available. It's still OK to wait until the theater or TV season ends, but it better be available online soon afterwards.

- Support the infrastructure. Once DivX supports some form of moderate DRM, Hollywood needs an iTunes-like experience for video. They should instantly make their entire catalog available to any service that wants to provide it on the same terms as DVD releases (minus the costs of physical distribution), spurring the same sort of innovation in that area as we've seen in music.

Irfan Khawaja has an essay which criticizes the "schizophrenic ambivalence" that characterizes the Critical Reception of Fahrenheit 9/11:

Thus Paul Krugman tells us in The New York Times that the film promotes "a few unproven conspiracy theories," and induces its viewers to believe "some things that probably aren't true." Having done so, he then praises the film's "appeal to working-class Americans" and its "public service" for having manipulated us in the right way.William Raspberry describes Fahrenheit 9/11 in The Washington Post as an "overwrought piece of propaganda," a "110-minute hatchet job that doesn't even pretend to be fair"-and for good measure, as dishonest, lacking in objectivity, and partially fabricated. That doesn't stop him, of course, from praising it for doing a "masterful job," for having the right "attitude" and for (literally) demonizing George W. Bush.

David Edelstein describes Fahrenheit 9/11 in Slate as disgusting, lamenting its "boorish, bullying" qualities, and describing it as "an abuse of power"; in the same breath, he tells us that the film "delighted" him, and that he "celebrates" its sheer panache.

Todd Gitlin's review in Open Democracy calls Fahrenheit 9/11 a "shoddy work": the film's "sloppy insinuations, emotional blackmail and all-around demagoguery," he argues, are an affront to one's "conscience," and make it the moral equivalent of a beer commercial. The same conscientious concern induces Gitlin to describe Fahrenheit 9/11 somewhat paradoxically as a moral necessity. Meanwhile, he lionizes Moore himself as a "master demagogue."

Juan Cole describes the film on his weblog as making "no sense," as "inaccurate" and as "full of illogic"; having said so, he goes out of his way to tell us that he found it "inspired." Stanley Kaufmann in The New Republic calls the film "slipshod in its making, juvenile in its trappings," and in considerable part, "contextually inane"-indeed, as "debased," "smug," and "regrettable." Having filled a column full of invective of this sort, he ends his review by praising Moore's fans for the "ardor" with which they've received his film.

Moore's film, we're told, is unfair, impolite, unsubtle, unwise, obnoxious, tendentious, and maddeningly self-contradictory—all [The New York Times'] Scott's terms, not mine. And yet, Scott insists, Moore is a "credit to the republic" for having made the film despite this. It seems not to have occurred to Scott that once you concede that crap like Fahrenheit 9/11 is a "credit to the republic," you've already conceded that the republic is itself a piece of crap—at which point it seems futile to insist that the film is but "a partisan rallying cry, an angry polemic, a muckraking inquisition into the use and abuse of power."

I have had a request for some time now to go beyond my anecdotal (and sometimes snarky) posts about liberal media bias, and deliver a more coherent critique. Mike F. wants to know whether I really believe that the media is biased, and if so, why I think that when outlets such as Fox News, the Washington Times, and Wall Street Journal exist. This topic has also been the subject of several e-mail discussions with Brad A. as well.

So I thought it worth spending a bit of my fourth of July weekend spelling out my reasoning when I say, yes, the media is liberal, and yes, it matters.

Before I do, though, I want to make clear that I don't think that liberal bias is the only (or even predominant) factor that leads to bad reporting. In fact, I think that there are three other main factors that contribute to sloppy, one-sided journalism:

There are also difficulties in dealing with a particular moment in time and how that relates to larger trends, for instance the current liberal frustration with being out of power in Congress, the executive, and by some accounts, the judiciary.

All this is even more complicated by the interplay between "objective news" and editorial opinion. If the New York Times fills it's op-ed section with liberal opinions (or the Wall Street Journal with conservative ones) but their "news" reporting is unbiased, are they part of the "liberal media"? What about cable news channels where news and commentary are not as clearly separated? Can we avoid assigning a label (liberal/conservative) based on editorial content? On the other hand, is it reasonable to believe that editors that select conservative columnists are going to be less selective in choosing and editing news stories? It's complicated.

So, I'm not coming at this from a simplistic model of the way the media works. But I do think that problems I've mentioned above are exaggerated and amplified by a insular and monolithic world-view, namely a liberal one, that dominates in journalistic circles. When a reporter, and all of her colleagues, are liberal, the meta-narrative that a lazy story will fit into will be a liberal one.

Anecdotally, it's easy to pick apart specific stories in specific papers or channels. But, admittedly, selected examples of purported bias, like the man-on-the-street interviews so often complained about, are not particularly compelling if you don't already believe the story line. But I do want to list a few anecdote-driven arguments that I do find somewhat compelling, before moving on to more substantive evidence.

For me, the cries from liberals of Fox News this, Fox News that, is simply more support for the idea that most media is liberal. In my view, Fox News is the mirror image of CNN, MSNBC, and the network news channels. Yes, it is right-of-center. Yes, it's commentary, tone and choice of stories, particularly in regard to the Iraq war, is more conservative than those of the other cable news channels. But it is no farther right of center than the other channels are left (if this causes some sputtering on your part, be patient and I'll return to this point below in the evidence section). In my mind, the "outrage" of Fox News' bias, should inform liberals more about the plight of conservatives before the advent of Fox News, than about the unfairness of the system. To those that would argue that CNN is just more "objectively true" than Fox News, I would respond that we've reached one of the fundamental difficulties in tackling media bias – the subjective nature of the labels ("conservative", "liberal", "biased", "objective"). Whether your epistemology has room for objective truth or not, you should at least be comfortable admitting that the application of the label "objective truth" is itself subjective.

Second, on one particular issue, the Iraq war, I have been struck by the non-stop flow of people returning from Iraq who claim that their experience does not match up with the view portrayed by the media. While these people, often military personnel, diplomats, or representatives on fact-finding missions, are certainly not unbiased themselves (they went there for a reason and, like all people, have an agenda), the consistent stories they tell and evidence they cite, leads me to conclude that the media is missing an important part of the story. Can I assign this failure unequivocally to bias rather than laziness? No. But the effort put into telling other parts of the story, leads one to presume.

Finally, there is the argument that all people cannot help but inject their personal viewpoints into their reporting. Yes, this is an argument against "objective news". Beyond the question of getting the facts right, a thousand subjective judgments go into the final product we call news. From story selection, to choice of interviewees, to editorial decisions, to headline writing and layout decisions (above-the-fold/below-the-fold), to vocabulary – each contains a potentially unconcious viewpoint. I was particularly struck by Brad A.'s example (admittedly making a different point) of the language choice (either latinate or vulgar) between the majority and the dissent in partial-birth abortion cases. At a minimum, these conscious or unconscious word choices will color the final product. And this is problematic when the evidence (see below) leads us to conclude that there are many more liberals in the news business than in the population. For (final, anecdotal) example, it's difficult (at least for us cynics) to see how an editor this vociferous in his partisanship could lead an unbiased news organization.

But enough anecdote and argument. Is there evidence that the news media is liberal? A first question, which again gets to the heart of the problem, is "What do we mean by liberal?" "More liberal than me" is obviously problematic. Self-reported liberals is equally difficult, because it just moves the subjectivity from the observer to the observed. More liberal than the average (median?) American, sounds right but has measurement problems. More liberal than the average human is probably less relevant for talking about US media, and even harder to measure.

Different studies have used different techniques, some fairly clever, to answer this question and I want to highlight a few of them here.

First, the Media Research Center has a round-up of surveys and studies that discuss the voting record of various groups in the media: White House correspondents, Washington bureau chiefs, Congressional reporters. Some of the information is old, but a particularly striking example is given in Elaine Povich's book, Partners and Adversaries: The Contentious Connection between Congress and the Media. According to a survey, 89% of Washington correspondents voted for Clinton in 1992 and only 7% for Bush. By contrast, 37% of the American public voted for Bush. To put it in perspective, fewer of the journalists voted for Bush than did voters in even the most liberal counties in the country. Even the county containing Cambridge, MA registered 19% for Bush.

The site, which again I want to point out assuredly has its own agenda, has plenty of other statistics.

More recent data can be found in this 2004 study conducted by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press and the Project for Excellence in Journalism. You can read the final report here [PDF]. There are other interesting things in the report, including journalists' concerns over a commercialized editing room, that are worth reading as well. The survey of 547 journalists found that 34% of national journalists consider themselves "liberal" versus 20% of the population at large. Only 7% considered themselves "conservative", versus 33% of the US population. While these self-reported labels are obviously problematic (for instance, are the 54% of national journalists who call themselves "moderates", actually conservatives who are afraid to say so or liberals who, compared to other journalists, consider themselves moderate), the survey points to views about religion as being a key differentiator between the public and journalists, with 58% of the public holding the view that you must believe in God to be moral, while only 6% of journalists do.

These facts argue strongly that the individuals in the media, the reporters, editors, anchors and correspondents, are more liberal than the average American. But what about their reporting? An argument could be made that, recognizing the prevalence of their bias, the journalists would bend over backward to be fair in reporting on issues, if only to allay the suspicion of bias. Perhaps we should expect conservative reporting from a liberal media. Then again, perhaps, as I argued above, we should expect unconscious liberal coverage despite best intentions.

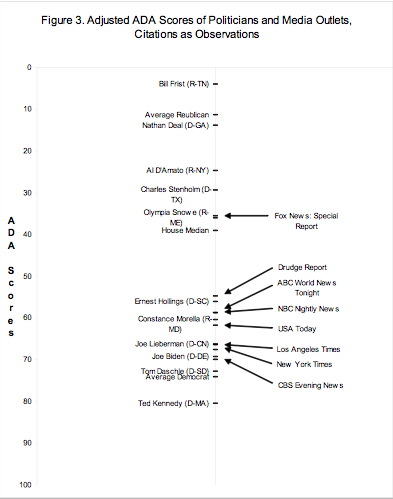

A final study from Yale University, recently released, and dicussed in this article tries to get at an answer to this question. The full report can be found here and is definitely worth reading to fully understand their methodology. The authors build on two previous works. First, the scores calculated by the Americans for Democratic Actions (ADA) which measure the "liberalness" of members of Congress based on how often they vote the ADA's side of the issue. A politician's ADA score (also known as a liberal quotient, or LQ) is often used to rank how far right or left she is, and the rankings tend to track, at least relatively if not absolutely, intuitive feelings of which members of Congress are "more conservative" or "more liberal" than others.

The researchers also build on previous work that tried to judge media bias based on how often they quote from "liberal" vs. "conservative" think tanks. This obviously begs the (perhaps less difficult but still vexing) question of which think tanks are liberal and which conservative. Whether the Brookings Institution is more liberal than RAND Corporation is a typical question.

The authors try to solve this problem by taking a period of time and looking at which think tanks members of Congress quote most often and matching that with their ADA score to assign an imputed ADA score to the think tanks, that rank orders them according to how far left and right they are. This method passes some basic plausibility tests in that the Family Research Council and the Heritage Foundation get very low scores (since they are quoted most often by hard-right members of Congress) while the Economic Policy Institute gets a high score (for being quoted most by very liberal members of Congress).

Finally, they took a sample of articles from major publications and counted the citations of the same think tanks. They made obvious corrections, like disregarding references that were only used to argue against the think tank's position. They used the metrics to give the media outlets a likely ADA score (using the maximization of a likelihood function – see the paper for details). The paper also has many other points about why this metric is appropriate (or at least the best available).

But before people claim that Amnesty International (11 points above House median) is a "legitimate" organization, whereas the National Right to Life Committee (24 points below the median) is just "bunk" and "propagandists", let me remind you of the subjectivity that we're trying to remove through this exercise. One man's propaganda is another man's gospel truth.

The authors were surprised by the results, which show that all media outlets tested, except for Fox News, were more liberal than the median representative in the House. In fact, Fox News was much closer to the median of the House than any of other news outlets. In their words:

We now compute the difference of a media outlet’s score from 39.0 to judge how centrist it is. Based on sentences as the level of observation (the results of which are listed in Table 8), the Drudge Report is the most centrist, Fox News’ Special Report is second, ABC World News Tonight is third, and CBS Evening is last.And here's the figure from the report:

Given that the conventional wisdom is that the Drudge Report and Fox News are conservative news outlets, this ordering might be surprising. Perhaps more surprising is the degree to which the “mainstream” press is liberal. The results of Table 8 show that the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, USA Today, and CBS Evening News are not only liberal, they are closer to the average Democrat in Congress (who has a score of 74.1) than they are to the median of the whole House (who has a score of 39.0).

If you have references to other studies (or even arguments) that refute these claims, please put them in the comments. In fact, I'd even be happy to see some anecdotes. For now, thought, here are some further readings:

You tell me if this headline is justified: New Swell of Insurgent Violence Rolls into Baghdad. Here are the news items contained in the article, in order:

Eric Johnson, a Marine who served in Iraq, has an interesting piece on the press coverage of the Iraq war entitled The Untouchable Chief of Baghdad:

Iraq veterans often say they are confused by American news coverage, because their experience differs so greatly from what journalists report. Soldiers and Marines point to the slow, steady progress in almost all areas of Iraqi life and wonder why they don’t get much notice – or in many cases, any notice at all.

Truly unhinged:

Republicans don't believe in the imagination, partly because so few of them have one, but mostly because it gets in the way of their chosen work, which is to destroy the human race and the planet. Human beings, who have imaginations, can see a recipe for disaster in the making; Republicans, whose goal in life is to profit from disaster and who don't give a hoot about human beings, either can't or won't. Which is why I personally think they should be exterminated before they cause any more harm.Luckily, it's just a theatre review, so we're not expected to take him seriously. Via InstaPundit.

Gross ethical violation spotted at the Times.

Now this is a bit disturbing, and I'm sure that I'd be upset if I thought my body was going to be used as a cadaver at medical school and instead this happened: Bodies donated to [Tulane] medical school were sold to army for landmine tests.

But I wish they'd get the story right. Doesn't it sound at least a little more respectable that the bodies were blown up to test protective gear against landmines and not to test landmines. I don't know... to me that seems like an important distinction that the headline misses.

The Associated Press finds an interesting spin on the Iraqi spy case: Accused spy is cousin of Bush staffer.

Hmmm. Interesting. She worked for four Democratic members of Congress (including, most recently, one who ran for President) and several newspapers (including the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, which hosts the article) but the real story is that she's "a distant cousin of... Andrew Card".

These kinds of stories are what drive the right-wing nut jobs to scream "Slander!", etc. But you have to admit, it's pretty absurd reporting.

Update: Okay, it just gets worse. It turns out that Andrew Card actually turned her in:

The U.S. official was not identified. But federal sources told NBC’s Pete Williams that the official was Card, Lindauer’s second cousin. The sources said it was Card who alerted authorities to his relative’s activities. A government official, speaking on condition on anonymity, later told The Associated Press that Card was the recipient of the letter.

What is this tripe?

"Dadburn," Rummy fumed, squinting through his wireless glasses and waving his shotgun in the air. "A trained ape could have found a little something in that stinking cesspool. Can you believe that tweedy blabbermouth David Kay came back without even a germ? Goodness gracious, wasn't he working for us?"Dick Cheney didn't answer. He was even more immobile than usual, in his jungle cammies in the field of the Rolling Rock Club in Pennsylvania. Nino, his partner in electoral manipulation and fowl assassination, was at his side, smoking and sipping Montepulciano from a silver thermos.

One thing Rummy admired about Dick. He never cracked under pressure. Look at Martha Stewart. When her story fell apart, she turned into a trembly bowl of Jell-O, something she would never be caught dead serving.

And she gets a paycheck for that?!?! It's not even funny. And I certainly don't see how it sqeaks by the ever-laxer "fit to print" qualifier.

At least the New York Times is keeping the level high. I just don't know what the hell they are thinking:

If seeking the presidency is like reaching for the stars, then why not look to the stars....

I'm impressed, they seem pretty spot-on to me. I guess that's the difference between accurate, individual readings by a professional and the stuff you usually see in the papers. (Link via OxBlog)

I've commented before on the FCC's move to deregulate media ownership, but that was before I had a blog on which to vent. I came down (fairly) solidly on the free-market side of the debate that raged on an e-mail list.

Now, Reason has a new article debunking the myth of media concentration: Domination Fantasies: Does Rupert Murdoch control the media? Does anyone?

According to Ben Compaine, the media industry compares favorably in competitiveness to the US auto, semiconductor and pharmaceutical industries. Another tidbit: the total number of stations owned by Clear Channel (1,200) is less than half the number of new stations started in the last 20 years (2,500 of a total of 10,500).

Overall, worth a read.

For those that I didn't spam with my thoughts before, click the link to read my e-mail from September, happily removed from the troublesome responses and salient points of those I was debating....

Well, after much hesitation about joining the fray, here's my 2 cents.While it may shock my wife to hear it, I agree with almost 100% of Alex's analysis, even though I'm sure our policy conclusions are pretty different. I wouldn't have said that capitalism and democracy are "contrary" -- I would have said "orthogonal", but that may be because I'm a computer geek. I actually think that they have a lot in common, since they both harness self-interest, decentralized decision-making, individual preference, and diffuse, tacit knowledge to create outcomes that are better than any one person (or elite group) could come up with. In my mind, they work for the same reasons. Yes, they butt heads in certain areas (like campaign finance, media, etc.) but, to paraphrase and extend Churchill, they are the worst combined economic/political system, except for all the rest.

But beyond that, contrary to Alex, no one worth listening to on the pro-capitalism, pro-business, pro-free-market side of the debate is actually arguing for full-on laissez-faire capitalism. That's a straw man argument from 125 years ago that's easy to beat up on but not really close to anyone's actual position. Similarly, very few on the pro-labor, pro-egalitarian, pro-welfare side of the debate are arguing that full-on central planning is a better idea than some form of market economy any more. Both extremes died in the laboratory of the 20th century -- or should have.

The question is, pragmatically, how do you strike the right balance to achieve your goals (and, of course, what are your goals)? Is it the income gap or absolute standards of living or the poorest, or the average standard of living that should matter? How much inequality is okay? How do you harness the engine of capitalism without losing control to the corporations? How do you provide a meaningful social safety net without "moral hazard" becoming a valid concern? These are all tough problems that reasonable people can disagree on.

I tend to come down on the libertarian, free-market side of the line for a few reasons. Skipping over the philosophical ones, the most important for this discussion is that the world is a dynamic place. All of the things that make 2003 a more pleasant (and healthier) time to live than 1903 or 1803 are here because of innovation, growth, progress, invention -- in short, change. And there's one thing that markets (and other decentralized, networked systems) are good at -- handling change. Central governments, on the other hand, tend to be pretty bad. Whether it's Soviet Gosplan trying to shuffle steel prices to take into account a coal shortage, or the US Patent Office trying to deal with gene sequence patent applications, or copyright law trying to deal with digital media, or the FAA with space flight, or Congress with Internet porn, or.... they tend to muck it up. At best they simply slow everything down, at worst they stymie innovation and force everyone down blind alleys. It gets even worse because companies with entrenched interests in existing regulations fight tooth and nail to keep them the way they are, clinging to the monopoly or competitive advantage the current rules give them. So I generally look sceptically at government regulations.

Now, all that being said, the FCC rule change is an interesting case.

First, rather than a market in tangible property, we have a market created from whole cloth in the licensing provisions of the Radio Act of 1927 and the Communications Act of 1934 that superceded it. Since you don't have real property rights, but rather renewable licenses in radio spectrum -- you can't just sit back and "let the market work". The government created the scarcity by limiting the number of stations in a geographic area and so needs to regulate the ensuing market. The same law that made the license in the first place, empowered the commission to protect the "public interest, convenience, and necessity." This is not the case in other markets with more Lockean property rights.

Second, I don't think the ownership rule changes are that easy to judge. To my point above about technological change, the current rules are either already out of date, or will be soon. Take the 1975 rule prohibiting "cross-ownership" of newspapers and radio or TV in the same market, for instance. Is this rule actually good for us now? With cable television, satellite TV, and the Internet, newspapers aren't the only place to advertise locally, and many are having a hard time surviving. Some major cities (including the 4th largest) have only one major paper. It's plausible that allowing cross-ownership will increase the number of papers available, which might be a good thing even if they are affiliated with a TV station. Also, the editorial departments of the newspapers could improve the quality of local news coverage on TV. I don't know if this will happen, but it seems possible. Plus, I can still use news.google.com and read any online paper in the world. With satellite TV and cable, why can Discovery, Inc. own 4 channels that I recieve, but a company can't own 2 broadcast channels in the same market? With streaming Internet radio, low-power radio, and XM satellite radio, how much longer is the artificial scarcity of radio broadcast licenses going to be relevant? Is 8 radio stations in a market really that much worse than six? Will it be in 5 years?

Third, in my mind if you really care about this stuff, you should care about the low-power radio rules, and make sure you support ("politically appointed") Powell there. Chairman Powell recently modified the rules to open up thousands of cheap licenses for low-power community radio stations -- a potentially major shift in how music and content is delivered. Maybe he "bought" these changes by caving on the ownership rules -- I don't know. Maybe that wouldn't be a good deal for us, the consumer -- again, I don't know. Regardless, Congress already tried to close this door once before with the Radio Broadcast Preservation Act of 2000, which put many roadblocks in the path of those trying to get the low-power licenses. It's likely that they'll try again -- so make sure any bill that you support to rollback the ownership rule changes doesn't also squash the new low-power rules. More choice is good for everyone.

So where do I come down on this one? I'm actually pretty conflicted. I don't want to see Clear Channel own 100 more stations any more that anyone else does. I'm not convinced that the rules are that great the way they are now, but I don't see a pressing need to change them either. Both the old rules and the new rules will have problems handling the future. I think the government's role as anti-trust watchdog is an incredibly important "check and balance" on the power of the private sphere, but I think our problems in the media space are much larger than just these rules over distribution. Technology will find a way to obsolete and replace the current means of distribution, so the rules governing the distribution aren't that important in the long run.

The larger issue, which no one in Washington wants to touch, is the control of the content. The six media companies that own all the content scare me much more than the distributors. And when they're the same company, it's their content that gives them their power. Increasingly strong copyright laws, protecting content in practical perpetuity, limiting the usefulness of our hardware and software, all bought by the lobbying of the big six -- that is the real danger.

So, yeah, maybe, oppose the rule change. But fight to repeal the DMCA, block the next Copyright Term Extension Act, stop the encroachment on fair use rights, donate to the EFF, etc., etc.

So the Senate has voted 55-45 to overturn the FCC ownership rule change. It's likely to face some opposition in the House, and the President may even veto the bill.

Just last week I had a rousing e-mail debate with some friends (and strangers) about media consolidation and specifically the new rules.

Here's what I said then, in the heat of the moment. I'll stand by most of it....

Skip down about halfway if you don't want to read the background, philosophical stuff that was part of the discussion.

I agree with almost 100% of AC's analysis [of capitalism and democracy], even though I'm sure our policy conclusions are pretty different. I wouldn't have said that capitalism and democracy are "contrary" -- I would have said "orthogonal", but that may be because I'm a computer geek. I actually think that they have a lot in common, since they both harness self-interest, decentralized decision-making, individual preference, and diffuse, tacit knowledge to create outcomes that are better than any one person (or elite group) could come up with. In my mind, they work for the same reasons. Yes, they butt heads in certain areas (like campaign finance, media, etc.) but, to paraphrase and extend Churchill, they are the worst combined economic/political system, except for all the rest.But beyond that, contrary to AC, no one worth listening to on the pro-capitalism, pro-business, pro-free-market side of the debate is actually arguing for full-on laissez-faire capitalism. That's a straw man argument from 125 years ago that's easy to beat up on but not really close to anyone's actual position. Similarly, very few on the pro-labor, pro-egalitarian, pro-welfare side of the debate are arguing that full-on central planning is a better idea than some form of market economy any more. Both extremes died in the laboratory of the 20th century -- or should have.

The question is, pragmatically, how do you strike the right balance to achieve your goals (and, of course, what are your goals)? Is it the income gap or absolute standards of living or the poorest, or the average standard of living that should matter? How much inequality is okay? How do you harness the engine of capitalism without losing control to the corporations? How do you provide a meaningful social safety net without "moral hazard" becoming a valid concern? These are all tough problems that reasonable people can disagree on.

I tend to come down on the libertarian, free-market side of the line for a few reasons. Skipping over the philosophical ones, the most important for this discussion is that the world is a dynamic place. All of the things that make 2003 a more pleasant (and healthier) time to live than 1903 or 1803 are here because of innovation, growth, progress, invention -- in short, change. And there's one thing that markets (and other decentralized, networked systems) are good at -- handling change. Central governments, on the other hand, tend to be pretty bad. Whether it's Soviet Gosplan trying to shuffle steel prices to take into account a coal shortage, or the US Patent Office trying to deal with gene sequence patent applications, or copyright law trying to deal with digital media, or the FAA with space flight, or Congress with Internet porn, or.... they tend to muck it up. At best they simply slow everything down, at worst they stymie innovation and force everyone down blind alleys. It gets even worse because companies with entrenched interests in existing regulations fight tooth and nail to keep them the way they are, clinging to the monopoly or competitive advantage the current rules give them. So I generally look sceptically at government regulations.

Now, all that being said, the FCC rule change is an interesting case.

First, rather than a market in tangible property, we have a market created from whole cloth in the licensing provisions of the Radio Act of 1927 and the Communications Act of 1934 that superceded it. Since you don't have real, private property rights, but rather renewable licenses in radio spectrum -- you can't just sit back and "let the market work". The government created the scarcity by limiting the number of stations in a geographic area and so needs to regulate the ensuing market. The same law that made the license in the first place, empowered the commission to protect the "public interest, convenience, and necessity." This is not the case in other markets with more Lockean property rights.

Second, I don't think the ownership rule changes are that easy to judge. To my point above about technological change, the current rules are either already out of date, or will be soon. Take the 1975 rule prohibiting "cross-ownership" of newspapers and radio or TV in the same market, for instance. Is this rule actually good for us now? With cable television, satellite TV, and the Internet, newspapers aren't the only place to advertise locally, and many are having a hard time surviving. Some major cities (including the 4th largest) have only one major paper. It's plausible that allowing cross-ownership will increase the number of papers available, which might be a good thing even if they are affiliated with a TV station. Also, the editorial departments of the newspapers could improve the quality of local news coverage on TV. I don't know if this will happen, but it seems possible. Plus, I can still use news.google.com and read any online paper in the world. With satellite TV and cable, why can Discovery, Inc. own 4 channels that I recieve, but a company can't own 2 broadcast channels in the same market? With streaming Internet radio, low-power radio, and XM satellite radio, how much longer is the artificial scarcity of radio broadcast licenses going to be relevant? Is 8 radio stations in a market really that much worse than six? Will it be in 5 years?

Third, in my mind if you really care about this stuff, you should care about the low-power radio rules, and make sure you support ("politically appointed") Powell there. Chairman Powell recently modified the rules to open up thousands of cheap licenses for low-power community radio stations -- a potentially major shift in how music and content is delivered. Maybe he "bought" these changes by caving on the ownership rules -- I don't know. Maybe that wouldn't be a good deal for us, the consumer -- again, I don't know. Regardless, Congress already tried to close this door once before with the Radio Broadcast Preservation Act of 2000, which put many roadblocks in the path of those trying to get the low-power licenses. It's likely that they'll try again -- so make sure any bill that you support to rollback the ownership rule changes doesn't also squash the new low-power rules. More choice is good for everyone.

So where do I come down on this one? I'm actually pretty conflicted. I don't want to see Clear Channel own 100 more stations any more that anyone else does. I'm not convinced that the rules are that great the way they are now, but I don't see a pressing need to change them either. Both the old rules and the new rules will have problems handling the future. I think the government's role as anti-trust watchdog is an incredibly important "check and balance" on the power of the private sphere, but I think our problems in the media space are much larger than just these rules over distribution. Technology will find a way to obsolete and replace the current means of distribution, so the rules governing the distribution aren't that important in the long run.

The larger issue, which no one in Washington wants to touch, is the control of the content. The six media companies that own all the content scare me much more than the distributors. And when they're the same company, it's their content that gives them their power. Increasingly strong copyright laws, protecting content in practical perpetuity, limiting the usefulness of our hardware and software, all bought by the lobbying of the big six -- that is the real danger.

So, yeah, maybe, oppose the rule change. But fight to repeal the DMCA, block the next Copyright Term Extension Act, stop the encroachment on fair use rights, donate to the EFF, etc., etc.

With that, I petered off into sleepless incoherence.