Let's say you are enamored with Whirlpool's Duet, the country's top-selling front-loaded washing machine. It is one of the more energy-efficient machines using about 227 kilowatt hours of electricity a year, according to a government rating that appears on the yellow Energy Guide sticker affixed to all new appliances. You can find one at Sears or other appliance stores for about $1,400. (Of course, the cost won't end there. Unless you buy a matching Duet dryer at about $900 to sit next to it, your laundry room will look like a squinty-eyed pirate.) The Duet washer would cost about $78 a year to operate compared with $161 a year for Whirlpool's $549 Ultimate Care top-loader, according to a downloadable calculator on the Department of Energy Web site (http://www.energystar.gov/index.cfm?fuseaction=find_a_product). But because the Duet costs so much to buy, the total cost of the front loader over seven years is $1,946, or $269 more than the Whirlpool classic top loader. Guess what? It makes economic sense to buy the more expensive machine. In theory, a dollar today is more valuable than a dollar in seven years. Therefore, you should be willing to pay $318 more for something that saves you $546 over seven years. (You can do this "present value" calculation at http://www.csgnetwork.com/presvalcalc.html). That calculation will be useful anytime you buy a product that promises future savings.Can you spot the howler? Because the upfront cost of Duet comes first, it should have to save you that much more than the cheaper model over the seven years. In other words, because a dollar is "in theory" worth more today, the Net Present Value (NPV) calculation works against the expensive model... but they've presented it as working in its favor. Two seconds of thinking about this showed me it couldn't be right. How could this end up in the "Your Money" section of the New York Times and not be caught? Update: I've been thinking about this a bit more and I just can't figure out what happened to get these paragraphs published in the NYT. Perhaps some radical last minute editing that accidently got rid of other sentences that would have explained it? I doubt it, but what in the world does the fact that "you should be willing to pay $318 more for something that saves you $546 over seven years" have to do with anything in the article? From the math I do, the Duet washer saves you $581 in energy costs over the seven years, but costs $851 more to buy. Where do the $546 and $318 come from? The closer I look the more this just seems like innumeracy on top of economic illiteracy.

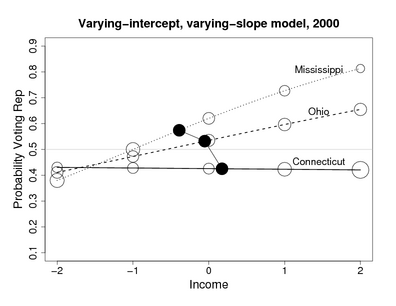

I actually think the graph is excellent – it packs a lot of information into a small space. The y axis is the percentage voting Republican in the 2000 election, the x axis is a quantile-based scale of individual income, the open circles denote the number of voters in each quantile for each state and the black circles show the mean income for the state.

So I'm with them so far, but then I thought... wait a second, what exactly is the "quantile-based scale" for income? A first glance, it's likely that it's a national scale because there explicitly are different quanitities shown in each quantile for each state – that wouldn't make a lot of sense if they were state-specific quantiles. Looking at the paper, I see this footnote on page 6:

I actually think the graph is excellent – it packs a lot of information into a small space. The y axis is the percentage voting Republican in the 2000 election, the x axis is a quantile-based scale of individual income, the open circles denote the number of voters in each quantile for each state and the black circles show the mean income for the state.

So I'm with them so far, but then I thought... wait a second, what exactly is the "quantile-based scale" for income? A first glance, it's likely that it's a national scale because there explicitly are different quanitities shown in each quantile for each state – that wouldn't make a lot of sense if they were state-specific quantiles. Looking at the paper, I see this footnote on page 6:

The National Election Study uses 1 = 0–16 percentile, 2 = 17–33 percentile, 3 = 34–67 percentile, 4 = 68–95 percentile, 5 = 96–100 percentile. We label these as −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, centering at zero so that we can more easily interpret the intercept terms of regressions that include income as a predictor.The assumption has to be that those are national income percentiles. And it's worth noting that they are most definitely not quintiles – they are very uneven. The paper's 0 and 1 include 61% of the electorate while 2 only includes the top 5%. Why these specific breaks are used is not stated, but it would be interesting to see how the results would change if different breaks where used. It also makes it difficult to visually interpret the size of the circles on the graph. But back to my main point: these are national quantiles. The problem with this is that I would posit that any "income-effect" on political persuasion would have a lot more to do with relative income within your peer group, and to the extent that it is absolute, would be modulated by cost-of-living adjustments. Looking at the chart again, and knowing that it's the poorest state, it seems clear that the people in income level 2 in Mississippi must be much less than 5% of the state electorate, while those in income level 2 in Connecticut must be more than 5%. For the sake of argument, let's say that income level 2 in Mississippi is 2% of the electorate, while in Connecticut it's 8%. I would expect the top 2% of a state's electorate to be pretty different from the top 8%, even if the absolute ranges were the same, simply because their relative "status" on the income scale is significantly higher. And that's before we take into consideration that after cost-of-living adjustment, the 2% of Mississippians in that top national ventile would feel much more rich than the 8% of Connecticutters in it. Likewise the bottom quantile must be much bigger than 16% in Mississippi and much smaller than 16% in Connecticut. Similar relative income and COLA effects would occur as on the top side. So here's an alternative hypothesis for the results they're getting: in each income quantile the Mississippians feel richer than the Connecticutters in the same quantile and therefore they vote Republican. This can be seen as a slight twist on the economic determinism argument, with subjective, relative income replacing objective, absolute income as the determinant. So would correcting for this make the effect they found go away? Probably not... or at least it's not clear that it would. But it would be interesting to see how the model held up on state-specific quantiles and/or COL adjusted ones. Would the top 2% of Connecticutters be more Republican than the top 8%, thus pushing the slope positive and diminishing the overall effect? I look to my statistical friends to catch any errors I've made in my logic.

Brink Lindsey, author of Against the Dead Hand: The Uncertain Struggle for Global Capitalism, has an interesting article on 10 Truths About Trade at Reason. Good ammunition for those of us who get in arguments about free trade with people every once in a while.

Dan Drezner has a boatload of posts about outsourcing and protectionism over at his site. First, there's this LA Times article about rebuilding the Bay Bridge, which go over budget by $2.7 billion:

This week, officials announced that the suspension tower alone would cost $1 billion more than originally expected.Now, this is obviously a big deal by itself for a state with a huge budget deficit. $400 million more for domestic steel. But the larger point is all protectionism acts the same way, costing the end consumer more. The problem is usually one of diffuse costs – we all pay $20 more here, $100 more there – and concentrated benefits – these three inefficient steel mills get to stay open another year. This giant public works problem just neatly aggregates the costs so we can see them all at one time. And they're huge.One reason, they said, is the state's "Buy America" rules, which dictate that Caltrans can use foreign steel on the bridge only if its cost is at least 25% less than domestic steel. In this case, the difference is only 23%, so the state must go with domestic steel. That added $400 million to the price tag.

Luckily, some states are thinking through the costs before they pass the bills:

When Kansas officials learned that food stamp questions were being answered by workers in India under a contract with an Arizona company, state senators added language to the budget requiring the work be done in the United States.But the language was deleted when negotiators learned it would boost the state's costs by $640,000, about 38 percent.

... from an international organization. From Asymmetrical Information, we learn that WTO has ruled against US Cotton subsidies.

Although some lawmakers, agribusinesses and farmers are worried by this development, hopefully we can use the ruling as an excuse to start to dismantle some of the most pernicious subsidies we have. From enriching a few large farmers, to causing severe water shortages, to encouraging wasteful use of marginal land, to locking out one of the only markets that poor third world farmers can compete in, to wasting billions of tax-payer dollars, cotton subsidies are some of the very worst of the awful set of quotas, tariffs and subsidies that practically define our agricultural policy.

Of course, Bush is playing his fair-weather free-trader role and vowing to fight for the American farmer and appeal the ruling. And Democrats are thrilled to go along with that or do even more.

But saner heads can prevail, right?

Tim Worstall has a post about grape tomatoes and the EU. Turns out, they're illegal. Not because of any sort of bio-engineering or genetic modification. No, simply because the EU did not list them in its regulations for what constitutes a legal tomato.

In fact, they are illegal for two reasons. First because they are not listed by name and, second, because they are too small to be called a tomator (only cherry tomatoes are exempt from the size requirements).

Oh the joys of regulation. (HT: Virginia Postrel)

Thomas Sowell, of Capitalism Magazine, has an article on Water Shortages. The shortages, driven by subsidies for farmers, specifically cotton farmers, are just another example of hidden harms caused by our absurd agricultural policy.

Preliminary figures are out for March employment. Payroll jobs rose by 308,000 in March, and figures for January and February were increased by 86,000.

I'll post more on this later. Specifically, I want to look at how the household numbers moved compared to the payroll numbers to see if it sheds any light on the argument raging over which to believe in times of recovery.....

Armed Liberal at Winds of Change points out a LA Times article about Kerry's thoughts on the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR):

Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kerry will announce a plan today in San Diego for reining in skyrocketing gas prices, saying President Bush has done nothing to stop increases that are hurting average Americans.Kerry's campaign said Monday night that the candidate would use a rally at UC San Diego this morning to propose increasing pressure on OPEC to produce more crude oil and to suggest that the United States should temporarily let supplies in its Strategic Petroleum Reserve be depleted, making more gasoline available for consumers.

I have to agree with AL's comments, "Truly, Deeply, Stupid":

So, let's see. At a time when our relations with the Arab states are as precarious as they have ever been, when Venezuela (another major source of imported oil) is in turmoil, and when domestic production is starting a long decline, Kerry wants to drain the SPI - the stock that exists to cushion shocks caused by cutoffs of imports (hence the name Strategic) so Soccer Mom and Soccer Dad can drive their H2 Hummers and Hemi Rams and not feel it in the pocketbook.

Meanwhile, I posted below an explanation about why gas prices are so high – contra Kerry, NIMBY sentiments about refineries and byzantine environmental regulations have more to do with it than Halliburton.

Update: Virginia Postrel links to her 1996 editorial in Reason about the "gas crisis" of the mid-nineties – still relevant today.

Russell Roberts argues against a tax on fat. Specifically, he addresses the "externality" argument, the idea that because obesity is extremely expensive to the public health system, we should regulate it:

But if obesity causes health problems, doesn't that justify government's involvement? After all, if we taxpayers have to foot the bill for some of those higher health care costs, don't we have the right to intervene in each others lives?This argument has been used to justify the on-going and growing regulation of tobacco. It's actually a lie. Smoking causes people to die earlier and relatively quickly, saving enough in Social Security expenditures to overwhelm the health care outlays. That actually justifies subsidizing tobacco rather than taxing it if you think that we should base public policy based only on the impact on government spending.

I think that logic is grotesque. But it's more than grotesque. It's dangerous. AIDS is a very costly disease, and some of those costs are born by taxpayers. AIDS is associated with certain sexual practices. Does that justify government regulation in the bedroom?

I don't think so. But my eating habits or yours don't justify the government's involvement in the kitchen, either.

Lynne Kiesling at Knowledge Problem, has an informative post on why gas prices are high and rising.

Dan Drezner has an extensive article in Foreign Affairs magazine that is worth a read:

Critics charge that the information revolution (especially the Internet) has accelerated the decimation of U.S. manufacturing and facilitated the outsourcing of service-sector jobs once considered safe, from backroom call centers to high-level software programming. (This concern feeds into the suspicion that U.S. corporations are exploiting globalization to fatten profits at the expense of workers.) They are right that offshore outsourcing deserves attention and that some measures to assist affected workers are called for. But if their exaggerated alarmism succeeds in provoking protectionist responses from lawmakers, it will do far more harm than good, to the U.S. economy and to American workers.

For a while now, I've thought that the current capital gains tax system is completely messed up. This is based on personal experience of trying to manage my stock portfolio as well as theoretical thinking about what the tax code is trying to achieve.

The biggest problem, in my mind, with the current system is the "cliffs" that occur at 1 year (and previously occured at 5 years). Under the new rules for 2003 (actually just after May 5, 2003 which is it's own little nightmare for reporting) the rate for "short-term" gains (held under one year) is your normal income tax rate. The rate for "long-term" gains (held one year or longer) is 15% (for people above the 15% income tax bracket) or 5% (for people in the 15% tax bracket). The 2003 changes also repealed the "super-long-term" category for assets held over 5 years.

Now personally, this has always been a pain in the ass when it comes to selling stock because you have the situation (and this has happened to me several times) where holding on to the stock one or two weeks more will drastically lower your taxes, but it doesn't fit in to your investment strategy (e.g. you think the stock could drop in the near term) or your liquidity needs (e.g. you need the money to put a downpayment on a house).

Theoretically, I understand that the cliff is supposed to encourage long-term saving and discourage speculation. It's arguable whether these incentives need to be there – free-marketers would argue that they distort the market and limit healthy arbitrage. But, in a post-Enron world, there's more support for regulations that discourage quick profit-taking and encourage the long view. (And there actually are some findings from behavioral economics that humans have non-exponential discount functions and might need encouragement to be more "rational".) So, for the purposes of this post, I'll assume that the long-term incentive is desirable.

In light of these facts, I have a new proposal...

Instead of a "cliff" system, with multiple rates to add progressivity, we should move to one formula that provides a continuous tax function. My proposed function would be:

(gain on asset sale) * (marginal income tax rate) * 365

tax owed = ----------------------------------------------------------------

A * (days asset owned) + 365

Here the marginal income tax rate would be calculated based on your adjusted gross income as if the capital gains were included as regular income. This is the same method that is currently used to determine whether you fit in the 15% bracket or not. A is an accelerator that could be modified by law to determine how fast the rate decreased over time.

While it seems a bit more daunting, here are the advantages that I see:

Potentially, there could be options involved to ease the filings of lower income people. For instance, you should always have the option to just treat the gain as ordinary income, and perhaps there should be an income threshold or a perentage of capital gains to ordinary income under which you wouldn't need to file a Schedule D. In addition, tables could be provided that approximated the formula for people below certain income levels. But, particularly given the complexity of the 2003 return with the cut-off date, etc., this doesn't seem drastically more difficult than the current April 15 nightmare.

In general, I'm opposed to social engineering through the tax code – at least the income tax that goes into the general revenue account. Usually, externalities that the government is trying to internalize in the market should be handled through more targeted user fees, etc. But if we're going to have a system that progressively tax capital gains while encouraging long-term planning, this seems to make more sense to me than the current system.

Comments? Too complicated? Bad idea? Things I haven't thought about?

First, Brad DeLong offers a more balanced view of the unemployment situation from Dana Milbank.

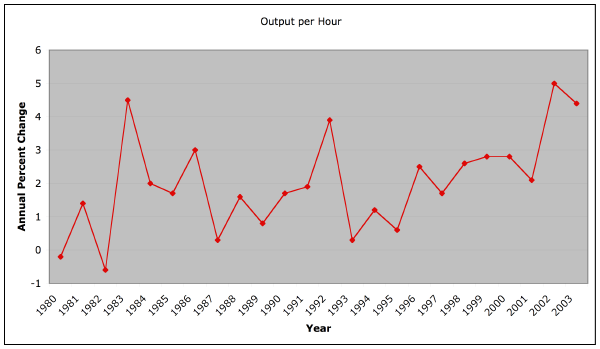

But for those of you who enjoyed all of the employment talk below, here's another graph from the BLS that goes to the heart of the matter:

This graph shows the number of unemployed and discouraged workers as a percentage of the labor force plus the discouraged workers. Discouraged workers are those who are no longer in the labor force because they were discouraged that they could not find a job. So this rate gives us a better indication of how many people would like to work, but can't (or couldn't) find a job.

Unfortunately, this data doesn't exist before 1994, so we can't get a more historical perspective on it. But it clearly shows that despite being significantly higher than the late nineties, this metric has moved significantly (in the right direction) since June 2003. The National Review would have done well to refer to this metric as well as the standard unemployment rate numbers.

While we're at it, here's another bit of under-reported good news. Average hourly wages of production, non-supervisory jobs (in constant 1982 dollars):

This should be the productivity gains kicking in, leading to higher average real wages even than during the bubble.

So I'm sticking to my not-all-doom-and-gloom position for now.

Brad DeLong attacks Jerry Bowyer of the National Review for running fast-and-loose with the truth over the employment figures. Bowyer trumpets the fall in the unemployment rate from 6.3% in June 2003 (when Bush enacted his latest round of tax cuts) to 5.6% in Feb 2004. But Prof. DeLong has a problem with the argument:

Since June 2003, the household survey estimate of the number of working age Americans has grown by 1.53 million.* During that same period, the household survey estimate of employment has grown by 700 thousand. In order for the employment-to-population ratio to remain constant, a 1.53 million increase in the working-age population needs to be accompanied by an 950,000 increase in employment. According to the household survey, we are 250,000 short since last June at what we need to maintain the ratio of employed Americans to the working age population. For those extra 250,000 (according to the household survey), the past nine months' labor market news has not been good.

If you look at the February BLS report on employment you'll see what I mean. The Table A reports use the Household Survey data that he's talking about. The official numbers on the BLS site are slightly different than Professor DeLong's and I can only assume he's applying some sort of correction to try to account for the fact that the BLS adjusted their population estimates downward (and thus the household survey numbers) in January 2004 based on new census estimates.

A quick look at June 2003 shows a Population Level, Civilian noninstitutional population, 16 years and over of 221,014,000. Feb 2004 shows the same figure at 222,357,000 which my calculator tells me is only an increase of 1,343,000 people (not the 1.53 million he claims). Looking at the same months, I see the Seasonally Adjusted Employment Level go from 137,673,000 to 138,301,000 giving us an increase of 628,000 jobs (not the 700,000 he shows). Again, his numbers may have a fudge factor to back out the Jan nudge.

But, using his argument, to keep the employment-to-population ratio the same, you'd have to add (1,343,000 * 0.623) = 836,689 jobs. So there is a shortfall of about 209,000 jobs. This corresponds to a fall in the employment-to-population ratio of 62.3 to 62.2%. Now here's the part I have a problem with. Prof. DeLong tries to use this fall in employment-to-population ratio to say that all is doom and gloom and the National Review's optimism is misplaced:

So what has happened? What has happened is that, for a number of different reasons, a lot of people have given up looking for work. The fall in the unemployment rate is not because the number of jobs has grown to encompass a larger share of the adult population, but because the fraction of the adult population who are looking for work has fallen as people have dropped out of the labor force.

So why, oh why (to borrow a phrase from DeLong) would we want to compare ourselves to the dot.com bubble, about which there has been no end to the handwringing? That was unsustainable, that was why there was a crash. It makes complete sense that many people who wouldn't otherwise work decided to get a job in the biggest boom economy in 50 years. Comparing the present economic climate unfavorably to that one is foolish, and at best will simply encourage policies that lead to more bubbles. Here's another chart for you, of productivity growth:

Again, historically high levels. That's pretty damn hard to do. High labor participation rates, low unemployment, low inflation, high productivity growth. Not to mention during a war, just 2 years after the World Financial Center was turned to dust.

Now, everything is not perfect of course, and I think we probably do need to extend unemployment benefits because there's a great deal of transition going on in our economy now. But there is room for a little optimism, even from the National Review. The last thing we need is for a drastic change of policy because we're wishing for the good ol' unsustainable days of the bubble.

To put this in perspective from the other direction, just think, if we had the EU's average 8% unemployment rate, we would have another 3.3 million people unemployed.

So for the moment, we should be optimistic. Barring external forces, we seem to be in a pretty darn good recovery, and I think Alan Greenspan is right, even more jobs will follow soon. (2.6 million by year end? Nope. But a bunch.)

But external forces are what we should worry about. I argued below that the trade deficit will be handled by the floating exchange rate (that's what it's there for) but that oil prices were a big part of the rise. It's possible that continued high oil prices will put a break on the recovery – we should be concerned about that. It's obvious that Saudi Arabia is trying to influence our foreign policy by controlling the supply of oil, so we'll have to live with the higher prices until a) we back down from some of our democratic initiatives in the ME, b) we elect a new president that makes nice-nice with the Saudis, or c) the Saudis realize we won't give and decide they need the money to badly to keep prices high. Regardless of politics, I think c) is best for our national interest over all.

Update: I have an additional post with more graphs here.

The Associated Press paints a bleak picture for trade in January: Record Trade Deficit in January Fuels Political Fight:

America's trade deficit hit a record monthly high in January, the start of an election year in which Democrats hope to use the swollen trade gap and the loss of U.S. jobs as campaign issues against President Bush.The Commerce Department reported Wednesday that the trade imbalance mushroomed to $43.1 billion in the first month of 2004, representing a 0.9 percent increase from the previous month.

For all of 2003, the trade deficit posted an annual all-time high of $489.9 billion, according to revised figures.

So the rise in the trade deficit was $365 million and Democrats are going to paint this as a clear indication that Bush's trade policies don't work.

But reading to the end, and perusing the actual report [PDF] we see that exports of meat and poultry fell by $255 million in January due to mad cow disease. In addition, oil & gas imports jumped $768 million dollars (6.9%) in January, mostly due to a $2.08 (6.5%) increase in the price of oil from December.

So the "jump" doesn't look particularly terrifying, especially since the 3 month moving average for the trade balance is actually lower than it was in April and May of 2003.

Alan Greenspan is right – the weakening dollar will mostly fix this problem over time, as US exports get cheaper and foreign imports more expensive. This is already working, as imports from Western Europe fell $5.4 billion (41%) in January. The country with the largest imbalance was China, with whom our deficit grew $1.6 billion (16.2%). Since they peg the yuan to the dollar, we're not getting any benefit from the cheaper dollar and they seem to be taking up some of the slack from the EU. It remains to be seen how this will play out over the next 8 months as trade with China will be a big campaign issue. My theory? China will make concessions on the yuan, both to appease their US trading partners and to slow their 9.1% growth rate (which they've already hinted may be too fast to handle).

A bigger problem for us will be continued high oil prices, which could slow the recovery. OPEC doesn't seem to like Bush very much so we could be in store for continued high prices for a while. On the other hand, the Gulf States are so addicted to oil revenue that they'll have to raise production some time – i.e. it's likely they couldn't survive a prolonged shortage like in the 70's.

Anyway that's my take. Another prediction: it's going to be increasingly hard to sort these things out give all the rhetoric that will be sure to fly from both camps over the next 8 months. That's a bit scary since it would seem that "sure and steady" (rather than "frantic and reactionary") is the right policy in the near term in order to protect the fragile recovery.

Why am I worried about reactionary policies? We end with the following quote from US trade representative Robert Zoelleck before the Senate Finance Committee (via Drezner):

“With America’s high standard of living, we cannot successfully compete against foreign producers because of lower foreign wages and a lower cost of production.” Perhaps this pessimism sounds familiar. It could very well have come from one of today’s opponents of trade, arguing against a modern-day free trade agreement. But in fact these words were written by President Herbert Hoover in 1929, as he successfully urged Congress to pass the disastrous Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act that raised trade barriers, destroyed jobs, and deepened the Great Depression.

My post the other day praising Tom Friedman's op-ed on offshoring got a lot more criticism than I expected, both in the comments and verbally. Julia obviously laid into me in the comments. And Mike F. told me over brunch at his parent's house that in an area where we mostly agreed I picked the one quote that he thought was unsupportable. T McGee asked "what percentage of [my] posts involve... making an argument by anecdote?"

So it's worth reexamining the quote and trying to explain what I took away from it and why I didn't have the visceral negative reaction that others did.

First, it's worth saying again why free trade is supposed to be good. It all comes down to the fact that in the absence of tariffs, the increase in consumer surplus will be greater than the decrease in producer surplus. Combine this with David Ricardo's comparative advantage – trade is beneficial to both countries even if all goods can be produced more cheaply in one country than the other; it's the ratio of the costs of production that matters – and neoclassical economics argues pretty strongly for it.

The current politically hot argument against free trade is that it "destroys" American jobs – there are or have been other arguments, but in this election year, environmental and labor standard critiques are on the back burner compared to the effects on domestic workers. Listen to Kerry, Gephardt, Edwards or even Bush if you want to hear this argument (in fact, listen to anyone except Gregory Mankiw and Alan Greenspan).

But there are two ways that trade helps the country in the long run. The first is by offering lower prices, both for companies and consumers. This makes everything from food to durable goods cheaper for consumers. It also makes American companies more competitive in the global market by make their inputs cheaper (and hence their marginal costs lower). This is why steel tariffs and sugar quotas backfire – steel-using companies are hurt by higher prices and candy-makers move to other countries. People (including me) talk about this effect fairly often – it's the standard argument for free trade.

But the other effect is just as real, even if harder to see and longer in coming. The idea is that, due to rising standards of living over time, demand is created in other countries for American goods. Because of comparative advantage, we live pretty high up on the food chain of production – we have huge advantages in creative, marketing, high-tech and many other areas that require educated workers and efficient capital markets. That's good for us because it makes us highly productive and wealthy, but the problem is that it takes rich people to buy the stuff that we produce well. So it stands to reason that having more rich people to buy our luxury items, see our movies, use our software is good for us.

I took Friedman's op-ed to be an argument, not for shareholder democracy, we all benefit because investors do, but for this second benefit of free trade. It was an argument that was part anecdotal, part statistical, and part (implicitly) logical.

Exports to India have gone up 72% in the last 12 years. And these outsourcing companies are (anecdotally) buying our products to help get their businesses up and running. And this is an expected benefit of free trade.

That's what I thought was worth highlighting.

No, the components for the Compaq computers probably aren't built in the US, but the marketing, R&D, integration testing, financing, industrial design and (maybe) final assembly is. The Microsoft software probably is written here. What makes the Coke bottled water valuable (the brand) is mostly made here. And all the call center reps and computer programmers probably go home and listen to US music, watch Hollywood movies, and wear American brand clothes.

Anyway, that was my reason for pointing to the op-ed. Maybe I left too much unsaid, maybe I selected a bad quote, maybe you all still disagree with me.

As to T McGee's criticism, while the people I link to or quote often include anecdotes in their arguments, I think a perusal of my economics category (or the front page) will show more statistics and rational argument than anecdotes. I'd be interested in knowing what percentage (and which posts) he thinks are anecdote-based. I try to use real data and economic arguments as much as possible, but anecdotes can be illustrative and persuasive in a way that raw numbers and logic can't.

Thomas Friedman argues about the hidden benefits of outsourcing in What Goes Around . . .:

I was prepared to denounce the whole thing. "How can it be good for America to have all these Indians doing our white-collar jobs?" I asked 24/7's founder, S. Nagarajan.Well, he answered patiently, "look around this office." All the computers are from Compaq. The basic software is from Microsoft. The phones are from Lucent. The air-conditioning is by Carrier, and even the bottled water is by Coke, because when it comes to drinking water in India, people want a trusted brand. On top of all this, says Mr. Nagarajan, 90 percent of the shares in 24/7 are owned by U.S. investors. This explains why, although the U.S. has lost some service jobs to India, total exports from U.S. companies to India have grown from $2.5 billion in 1990 to $4.1 billion in 2002. What goes around comes around, and also benefits Americans.

This is in addition to the more obvious benefits to American consumers (e.g. shorter hold times and better service) and American businesses (cost savings to keep them more competitive globally).

Good to see someone getting past the demagoguery.

Below, I made the claim that trying to shoot for "balanced trade" would slow growth. Well, why is that so bad?

The Wife and I often have discussions about economic policies, whether about the European economies or free trade, where the issue of growth comes up. She's quick to point out that "growth" is a socially-constructed, capital-inspired concept of a consumerist society, and that there are conceivably other equally valid, even more worthy, goals for a society to have than economic growth.

The problem that I have with this argument (as well as similar ones by the anti-globalization left, the nativist right, and neo-luddite, sustainable development folks) is that a lot of things that these people consider good (e.g. the modern welfare state, social security, health care, environmental protection, etc.) are predicated on a continued high rate of growth.

We will eventually have to face the music on our national debt and our impending Social Security and Medicare bills (especially if we keep raising the benefits) but the only thing, the only thing, that makes the concept tenable that we will face that reckoning without a major disaster, is the possibility that our economy can continue to grow at a such a rapid pace that past commitments become small compared future earning potential. Within our current mode of spending, the country has to be like the lawyer whose tens of thousands in school loans are quickly dwarfed by her seven figure salary.

Whether this eventually turns into a Ponzi scheme will be determined by how many additional commitments we make and how fast technology, the ultimate arbiter of productivity, can continue to advance. But, there is no other way, and there is no going back to a pre-growth society (if there ever was such a Rousseauian locale) without serious trauma to everything we (at least I) hold dear.

What "balanced trade" (whatever that actually means and however it would be enforced) is likely to do, is slow growth and make the eventual reckoning come sooner and be more painful.

Those of you who used to watch Moneyline and now watch Lou Dobbs Tonight may have been as amazed as me to see him turn into a rabid protectionist with his "Exporting America" segments. Watching the show, and the scrolling list of companies that are "exporting American jobs", the cynic in me presumes that his demagoguing and fear-mongering is about ratings – making outsourcing/offshoring his issue.

This transcript of his interview with James Glassman is worth reading (if only for the animosity). Obviously, I side with Glassman on this one. Our goal should be in easing the transitional pain for those workers whose jobs are lost (both through technological change and free trade) rather than striving for some kind idealized "balanced trade" that will most likely simply either lead to slow growth down the line or further entrench companies that can exploit the new rules.

Drezner, from whom the links come, has more on outsourcing here.

Anyway, here's the transcript:

DOBBS: Well, my next guest takes a decidedly different view. James Glassman wrote an article this week that begins by asking, "What Has Gotten Into Lou Dobbs?" In it, he takes issue with our extensive reporting here on "Exporting America," our conclusions and positions.Glassman says our list of companies sending American jobs overseas, which we update here every night and post on our Web site, include some of America's most innovative companies. James Glassman is a resident fellow with the American Enterprise Institute and joins me here in New York.

Jim, that was quite a little article.

JAMES GLASSMAN, RESIDENT FELLOW, AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE: Well, I think it was quite accurate.

DOBBS: OK, let's start with the accuracy.

The fact is that we are seeing hundreds of thousands of jobs being outsourced on the basis purely of a corporation's interest in achieving the lowest possible price for labor. Does that make sense to you?

GLASSMAN: Lou, that is called trade.

And we have been doing it for hundreds of years.

(CROSSTALK)

GLASSMAN: You majored in economics at Harvard. You understand that Adam Smith, David Ricardo showed that trade is good for both parties.

DOBBS: Absolutely.

GLASSMAN: So outsourcing, offshoring, whatever you call it, it is always called by something different during different generations -- those are the words right now. But it's trade. And it's good for the Indians and it's good for Americans.

DOBBS: OK. Let's assume that trade is good, because here no one has argued otherwise.

But what we have argued is that trade that is not mutual, mutually beneficial, doesn't make a lot of sense. We're looking here -- since you brought up trade, we'll go back to outsourcing those American jobs. We are looking at a half-trillion a year current account deficit.

GLASSMAN: Right.

DOBBS: How good is that?

GLASSMAN: It's not good. It's not bad.

We have, for the last 20 years, run a trade deficit. And by coincidence, for the past 20 years, we have had by far the greatest economy in the world. We've got an $11 trillion economy. We're bigger than the next five countries combined. We've got a 5.6 percent unemployment rate, compared to 10 percent in Germany. I think we're doing fairly well.

The reason we have such a large trade deficit is, we're doing a lot of importing, while the rest of the world, which has a worse economy, is not able to buy. That's the problem.

(CROSSTALK)

GLASSMAN: If you want to have a trade surplus, Lou, the best way to do it is to plunge the United States into a recession. If we don't buy anything, hey, we don't have a trade deficit anymore.

DOBBS: What is it with you people?

GLASSMAN: You people? What do you mean?

DOBBS: You people who seem to think there's only way for trade to work. Why in the world are you so opposed to the idea

(CROSSTALK)

DOBBS: Please, Jim, I let you finish.

GLASSMAN: Yes. Well, go ahead.

DOBBS: Thank you.

You could not conceive of the idea of restoring a manufacturing base to this country to actually manufacture products and export them?

GLASSMAN: Lou, over the last 10 years, we have manufactured 40 percent more than we did 10 years ago. Manufacturing is doing well. Jobs change. This is a dynamic society.

Now, the thing I'd like to -- the thing I would like to say is, free trade is much better than the alternative, which is no trade or obstructed trade.

(CROSSTALK)

DOBBS: Wait, Jim, you are far too smart to do something like that. There is not simply a Hobson's choice between free trade and no trade. I just offered you one, a mutuality of interest, mutual trade.

GLASSMAN: That's the idea of the World Trade Organization.

DOBBS: It may be the idea of some in the World Trade Organization. It is not the practice.

We have got 11 years experience with NAFTA. We have 10 years experience under WTO. It isn't working, Jim? What part of that don't you get?

GLASSMAN: It's not working?

DOBBS: It's not working.

GLASSMAN: Then why is the American economy as robust as it is?

DOBBS: Tell people it's robust.

(CROSSTALK)

DOBBS: Tell those 15 million people out there who can't

(CROSSTALK)

DOBBS: No, look in the camera, tell those 15 people out there who can't find a job right now...

GLASSMAN: I prefer to look at you. And let me say this.

This is a huge economy. I have tremendous sympathy for people who lose their job and are in pain. And for those people, we need to concentrate on helping them. How do we do it? We do it through job retraining. We do it through...

DOBBS: What are you going to retrain them for, Jim? You're a smart guy.

GLASSMAN: What do you mean what I am going to retrain them

(CROSSTALK)

DOBBS: What are you going to retrain them for? We're exporting many, many jobs.

(CROSSTALK)

DOBBS: We're exporting radiologists.

GLASSMAN: How did we retrain blacksmiths when the automobile came in?

(CROSSTALK)

GLASSMAN: Forty percent of Americans worked on the farm. Today, it's 2 percent. We produce far more agricultural goods than we ever did. We export agriculture.

(CROSSTALK)

DOBBS: Do you want to go back to policies of the 1850s in this country?

GLASSMAN: No.

(CROSSTALK)

DOBBS: Well, then why are you quoting these metaphors?

GLASSMAN: Because I'm trying to tell you, this is a dynamic economy.

DOBBS: Well, I think we understand that.

GLASSMAN: Every week, Alan Greenspan, in his testimony...

DOBBS: There's no fool here again, OK, no fool watching, no fool here listening.

Let me say this to you. David Ricardo, as you well know, never considered a world in which you were exporting American jobs to produce services and goods for reexport to the United States. It was never considered.

GLASSMAN: I really object to this term exporting American jobs.

DOBBS: Well, wait a minute.

(CROSSTALK)

GLASSMAN: It's not as though we start with 100 jobs. They have 100 jobs. We send a few. Our jobs have been on the rise for the last 20 years, enormously. We have 130 million people working in the United States.

DOBBS: Well, it's actually

(CROSSTALK)

DOBBS: ... million, but that's all right. GLASSMAN: Every week, as Alan Greenspan said in his testimony, a very interesting statistic for your readers.

(CROSSTALK)

DOBBS: They're viewers.

GLASSMAN: For your viewers and readers, right, in "U.S. News."

Every week, one million Americans leave their job, but one million Americans take a new job. It is that dynamism....

DOBBS: Jim, Jim...

GLASSMAN: It is that dynamism that drives the American economy.

DOBBS: American corporations are shipping jobs overseas for one reason.

GLASSMAN: They are not shipping jobs. And I really object to this rogue...

DOBBS: They are not shipping jobs?

GLASSMAN: I really object to this rogue's gallery of America's greatest companies: Intel, Pfizer, Amazon.com

DOBBS: Shipping jobs.

GLASSMAN: You were once a journalist. You know the accuracy.

DOBBS: Is IBM shipping any jobs overseas? Is IBM?

GLASSMAN: It's creating jobs at home and it's employing people overseas. Just as Honda, you have Congressman Brown here.

DOBBS: I've got to tell you something, if you continue to this...

GLASSMAN: there are 13,000 Honda jobs in Central Ohio. Honda is the largest private employer in Central Ohio.

DOBBS: What's that got to do with...

GLASSMAN: I was wondering whether you would like to stop, that, too.

DOBBS: If I wanted to stop that, Jim, I would say I wanted to stop it. There's no difficulty getting my opinion on something. That is a transplant in a market in which it is brought, it's factories of production. It is not analogous in any way to IBM shipping 10,000 jobs to India solely for the purpose of achieving lower wages.

GLASSMAN: No, no, no. Solely for the purpose of achieving lower costs.

DOBBS: All lower costs are I achieved by what means?

GLASSMAN: All businesses strive to cut costs. And why do they do that? In order to increase their profit so they can reinvest their profits into growth.

DOBBS: Let me review the bidding war, Jim, very quickly. What you are refusing to acknowledge, a half trillion dollar current trade deficit. We are importing capital. We are squandering our wealth on a short-term basis, corporate America and U.S. multinationals are shipping jobs for only one reason, not for greater productivity, not for efficiencies, those are purely code words for cheaper labor costs and you know it and you won't admit it.

GLASSMAN: Absolutely -- no, of course I'll admit it. Obviously any business...

DOBBS: Then, how can you support it?

GLASSMAN: ...every business is trying to lower its cost. But by finding laborers in other countries and lowering those costs, they are able to reinvest in their own business.

DOBBS: OK, I want to show you something, Jim.

GLASSMAN: And increase business at home. They have done this consistently.

DOBBS: Let me show you what Jim Glassman wrote, if we could have that, which piqued my interest when I read it. "Once a sensible, if self-important and sycophantic, CNN anchor, he has suddenly become a table thumping protectionist."

Do you think I'm a protectionist?

GLASSMAN: I do. I really do. And I think the worst thing about it. I think the worst thing about it is, that you know economics. You do know economics. And you understand comparative advantage.

DOBBS: And what is it that...

GLASSMAN: You understand Adam Smith. You understand the trade benefit both sides. You know that. I wish you would concentrate your tremendous intelligence...

DOBBS: That statement is wrong. It's flat wrong.

GLASSMAN: Lou, I wish you would concentrate your intelligence...

DOBBS: When you are carrying a half trillion dollar trade deficit, it's not benefiting both sides. That's precisely the point. If it were I would...

GLASSMAN: Of course it benefits both sides. The United States is the most...

DOBBS: Do you realize there are 3 trillion dollars in IOUs held by foreigners against U.S. assets? Does that trouble you.

GLASSMAN: The United States is the most robust economy in the world.

DOBBS: You can keep doing it.

GLASSMAN: Obviously, we have problems.

DOBBS: You talk like a cult member. There's a mantra, you say market, you say largest and dynamic.

GLASSMAN: I don't think I've said market yet.

DOBBS: And it simply removes the need for rationality.

GLASSMAN: I just wish you would devote your considerable intelligence what I think is the biggest problem with trade, which is alleviating the pain of the people who get caught. Trade definitely has more benefits...

DOBBS: I am trying to stop the pain before it continues and that's what has got to be addressed. And you are too smart to buy in as a sycophantic response to your corporate bosses and say, you know whatever you want to do, whatever the American enterprise needs to do.

GLASSMAN: To have real economists on the show to discuss these things. People like Katherine Mann who has done a study which shows that computer jobs are rising in the United States.

You talked to Katherine Mann?

DOBBS: We have talk to...

GLASSMAN: Michael Beldon at NC State...

DOBBS: Don't waste our time running through a litany of...

GLASSMAN: I'm talking about facts.

DOBBS: Here are the facts. Half a trillion dollars in a current account deficit. Hundreds of thousands of jobs being shipped overseas, as you acknowledge, by cheap labor costs.

GLASSMAN: I don't consider it shipped overseas. That's not what's happening.

DOBBS: You may not, that's my word. And the fact is, it is exactly what is happening and why you won't acknowledge that is beyond me. Where do you want the United States economy to be in ten years? You can't talk about jobs to retrain.

GLASSMAN: I want it to grow 3 to 4 percent a year as it has done in the past 20 years. Partly because...

DOBBS: And how much of the GDP do you want to be imports? How much of that GDP do you want to be imports? GLASSMAN: I really don't know. I think that's up to individual Americans to determine how much do they want in imports.

DOBBS: Mr. Market...

GLASSMAN: If they don't want to buy goods from overseas, they have that choice. If they don't want to buy Japanese cars they have that choice.

DOBBS: You don't think there should be a balanced trade approach? Balance trade, protecting American jobs.

GLASSMAN: I don't know what that mean.

DOBBS: You don't know what it means?

GLASSMAN: I really don't know what balanced trade means.

DOBBS: Watch the show some more, Jim, we're going to make it clear.

GLASSMAN: Thanks for having me on.

DOBBS: Good to have you here, Jim.

Tonight's thought is on opinion. You just heard a couple. "Few people are capable of expressing, with equanimity, opinions which differ from the prejudices of their social environment, most people are incapable of forming such opinions." We have demonstrated the truth again of Albert Einstein's words.

Wired has an article on The New Face of the Silicon Age, about outsourcing programming jobs to India. Worth a read.

I was interested to see that my alma mater was among the US companies and institutions using Hexaware, the featured company, for outsourced programming projects.

While I know these job movements are painful for people and they are sure to be vocal about that pain as the election approaches, it's important to consider two things:

One of the things that I get to see in my job is just how bad the software systems and technical infrastructure is at large companies – even in competetive ones that you'd think must do a better job. But it's just too expensive for them to update their old, broken, inflexible systems because it requires thousands of hours of integration, custom coding, tweaking and testing — all of which translates to millions of dollars at US salaries.

At some price, though, the demand will start to explode and I believe that there's a huge productivity spurt waiting to be unleashed by cheaper access to good, customized, tested software for businesses. Perhaps opening the doors to these gains to the thousands of small businesses that currently make do with ill-fitting off-the-shelf products. Everyone will win because of this – but, of course, the gains will be more diffuse, harder to tally, and make worse copy than the pains.

In the meantime, there's the question of what all of us American code-jockeys will do. Some have argued that we'll all end up in creative jobs. Others, that we'll all just move up the chain to design and project management – all that cheap code isn't going to design itself! Others, including Frederick Turner, say that we're moving to a "charm economy", whatever that means. Still others, pointing to the "lump-of-labor" fallacy, think the increased demand for software and services will make room for everyone in the industry.

I have to confess that I don't know what the next thing is, but it's worth remembering that there probably will be one, no matter how painful it is to get from here to there, and in the meantime some good will come of it too.

Update: Dan Drezner has a post on the related subject of Gregory Mankiw, chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, testimony to the Joint Economic Committee of Congress, during which he defended outsourcing of service jobs. He then has a good round up of Democratic reaction. As expected, they are seizing on this issue for the 2004 election, moving steadily away from the Clintonian free-trade wing and back toward Gephardtian protectionism. Drezner's not pleased with Kerry's comments in particular.

I posted about the GapMinder site last night, but I've had a chance to play around a little more on their site. They have some great little applets to explore the changes world development over the last 30 years.

Here's a particularly slick one showing income distributions. Check it out — they do a great job of giving you control of graph and letting you see change over time.

Alex Tabarrok at Marginal Revolution points out some health and education charts from the GapMinder site.

Here's an interesting one on child mortality vs. GDP per capita:

They manage to pack an amazing amount of information into that one chart: circle size indicates population, and colors the geographical region. (Click on the link to see a larger version). While it's no March of Napoleon, Edward Tufte would be proud. It's obviously a remarkably straight line (on a log scale for both variables) but a couple of other things stand out.

First, as expected, Sub-Saharan Africa fares poorly.

Second, if you combine this chart with this one that I previously linked to:

it's clear that China and India have moved significantly to the right (in both graphs) in the last 20 years. (Less because of the actual numbers – it's hard to compare 1996 dollars vs. 2002 PPP dollars – than as implied by the growth rates). While I don't have statistics from 1980 to back it up, it seems logical that the high growth would have translated into significantly increased infant survival statistics during that time — one of the payoffs of globalization. The old chart also reinforces the plight of Africa. Negative growth rates combined with AIDS and corruption will probably keep their mortality rates high for some time.

Third, the USA is noticably below the trend line even though it's near the top in GDP per capita. Explanations I've heard for this include both our immigration policy, which drags down the statistics as compared to the relatively "closed" countries that also grace the upper-right of the graph, and our semi-private, semi-public health system, which arguably puts to little emphasis on pre-natal and infant care as compared to the socialized care in Europe.

Well, I mentioned below that I had corresponded with Julian LeGrand, the author of Motivation, Agency, and Public Policy, by e-mail. I posted a (longish) review of his book below, but I wanted to post my e-mail in case anyone found it interesting:

From: Richard Vermillion

Sent: Wed 07/01/2004 06:53

To: Legrand,J

Cc:

Subject: Motivation, Agency, and Public Policy

Professor Le Grand,

I just finished reading your book, Motivation, Agency, and Public Policy, and I wanted to let you know how much I enjoyed it. The framework you propose, analyzing policies based on their implicit assumptions about human behavior, is truly useful in an area typically dominated by useless Left/Right dichotomies. And while I would have hoped for some additional technical content, I would certainly trade it for the level of accessibility and readability that you achieved. I only wish someone would analyze US policies and history through the same lens.

I had one question/comment about the "backward-bending" supply curves that you discuss in the Annex to Chapter 4. I was struck by the similarity of this curve to the curves that describe aggregate labor supply in the presence of child labor. As originally described in Basu and Van (1998), if you assume the luxury and substitution axioms, you get a supply curve similar to the S-shaped ones you show. (Actually, they tend to look slightly different because they assume inelastic supply at the adult clearing wage and the child clearing wage, but they still provide multiple equilibria). López-Calva (http://www.nipnetwork.org/docs_meeting2000/Calva.PDF) extended this work and proposed a model that assumes "that a parent who sends her child to the labor market is likely to face a social stigma that reduces her own welfare" and that the "stigma is lower the higher the aggregate incidence of child labor", resulting in similarly shaped curves.While household decisions about child labor would seem to have nothing to do with "knightly" provision of social services, the similarities in results seem too enticing to ignore. First, both describe two modes of supply, the transition between which is governed by a threshold and a social norm. In knightly supply, the threshold is based on self-sacrifice and the positive norm is altruism; in child labor, the threshold is based on subsistence consumption and the negative norm is a stigma for sending children to work. Second, by providing multiple equilibria, both are open to criticisms of exploitation. Finally, because of this, policy-makers have an interest in manipulating which mode dominates, and yet sometimes have difficulty doing so.

Anyway, my question is, have you considered these similarities? Is there something that relates these two things at a fundamental level, or is it just an interesting coincidence? Are they just examples of relatively mundane crowding-out, or do they say more about how norms tend to interact with rational utility maximization?Thanks for the excellent work, hope these comments are relevant.

Excuse the first paragraph — while I meant everything I said, I was also trying to be nice since I don't know the guy. Anyway, I don't feel comfortable posting his reply, since I didn't ask him before hand, but basically he said that he read the paper that I pointed him to and definitely thought there was something to it and asked that I keep him informed if I decided to do anymore "work" on the subject. He obviously had me confused with someone who does this for a living, but I'll take it as a complement....

The Financial Times has a story on European competitiveness:

Europe's apparently doomed attempt to overtake the US as the world's leading economy by 2010 will today be laid bare in a strongly worded critique by the European Commission.The Commission's spring report, the focal point of the March European Union economic summit, sets out in stark terms the reasons for the widening economic gap between Europe and the US.

It cites Europe's low investment, low productivity, weak public finances and low employment rates as among the many reasons for its sluggish performance.

The draft report, to be published by the Commission today, warns that without substantial improvements "the Union cannot catch up on the United States, as our per capita GDP is 72 per cent of our American partner's".

While economic growth is not the be-all-end-all, as The Wife is wont to say, it's interesting that they are missing their own goals. It seems they have a choice to make: abandon attempts to be the largest economy in the world, or remove some of the regulatory shackles that hinder investment, entrepreneurship, and productivity growth.

Julian Le Grand is Professor of Social Policy at the London School of Economics. His latest book, Motivation, Agency, and Public Policy: Of Knights & Knaves, Pawns & Queens, is an examination of the implicit and explicit assumptions about human behavior that underly the public policy prescriptions of both ends of the political spectrum.

As the title suggests, Le Grand posits two axes upon which to chart these assumptions: motivation and agency. He then introduces the "characters" of the subtitle to label the extremes of the axes. "Knights" are motivated by altruism and the spirit of cooperation, while "knaves" are self-interested utility maximizers — the kind of actors touted by public choice theorists. Agents are further divided into passive "pawns", cogs in the public service machine, and active "queens", empowered to make choices and free to act.

He demonstrates that this framework is interesting by examining how various policies promoted by the Left and Right, or as he calls them, the social democrats and neo-liberals, make different assumptions about where people fall (or should fall) on these axes. Social democratic policies tend to assume that service providers (politicians, bureaucrats, public servants) will be knightly while benficiaries will be pawns. Neo-liberals assume the opposite: producers are knaves and consumers should be queens.

Unfortunately, he continues in this vein and treats the two axes fairly differently, almost as two separate, one-dimensional explanations, focusing on motivation for service providers and agency only for recipients. It would be interesting to have the framework fleshed out to examine how both roles can move in this two-dimensional space.

In addition, while he takes a descriptive approach to the motivation axis, his treatment is almost completely normative with respect to agency. He takes it as given that policies should empower citizens and treat them as active agents in their implementation. While libertarians and classical liberals would certainly agree with this assertion, it seems to beg the question to some extent — those who believe that the collective good must come before individual choice may reject this starting point.

Le Grand could have bolstered his argument by showing that policies must take into account individual agency to be effective, i.e. a descriptive argument that showed how policies that treat citizens as pawns are likely to fail. The normative argument could have followed strongly on this consequentialist base.

This conceptual framework is laid out in the introduction. The three subsequent sections focus on Motivation, Agency, and Policies, respectively.

As mentioned above, his theory of motivation focuses mainly on the service providers, examining how they fall into the categories of altruistic "knights" and self-interested "knaves".

He describes how communal spirit after the Allied victory in WWII led, at least in the UK, to the renewed belief in man's ability to set aside selfishness and act in the interest of the community. This, in turn, led to the great movement in social democracy in England in the 50's and 60's. Studies and literature from the period claimed that not only were systems that relied on voluntary cooperation and altruistic motives more desirable from a normative point of view, they were actually more efficient. The most famous of these is Richard Titmuss' study of blood donors in Britain's all-volunteer system and his comparison to "market" systems as used in America.

Failures of these systems to live up to the promises (including the eventual need to import large quantities of blood from America) led in the late 70's and 80's to their replacement by quasi-market systems. These programs, brough about as part of the Iron Lady's conservative reforms, attempt to appeal to providers' self-interest to increase the quality, quantity, and efficiency of public services provided.

Le Grand then goes to the evidence to determine which kinds of programs actually are more effective. He starts from the assumption that, as long as they work, programs that promote and rely on altruism should be considered morally superior and better for society. He brings to bear some evidence from studies that show that market forces can actually remove people's willingness to contribute to the greater good — the collectivist fear that markets corrupt mankind and are, in fact, the source of, rather than the solution to, selfishness. He contrasts this with the hard-to-deny efficiency of market systems, particular in comparison to the failing social democratic policies of the 70's. He also cites studies that show that some incentives can increase altruistic behavior in some circumstances, including one of home care professionals in Britain who were given a small stipend for their time.

From these interesting but conflicting studies, he comes up with a compelling, but unfortunately very speculative, argument for an S-shaped supply curve for knightly service providers. He argues that small incentives will increase the supply of communal service as the implied recognition encourages knights to provide more services. At a critical threshold, he argues, the incentive overpowers the sense of sacrifice that drives the altruistic behavior and the supply actually decreases. Finally, full market-based incentives lead to an upward sloping supply curve based only on self-interested utility maximization. This is an attractive story, one I find plausible and compelling, but it seems to be based only on a small number of inconclusive and contradictory studies in different areas of "communal service". It would seem to be a promising area for future research, but it's also a tenuous foundation on which to build your theory of motivation.

Despite that, Le Grand tells an interesting story based on this theory and discusses some of the issues that arise because of the multiple equilibria that this "backward-bending" supply curve generates.

He ends by arguing for what he calls "robust" policies that encourage knightly behavior when possible, but also work in situations where knaves dominate. He leaves this as a vague idea in the theory section, but makes it (a bit) more concrete in the Policies section.

Le Grand's theory of agency focuses mainly on the recipients of public services, clustering them into active "queens" and passive "pawns". He starts from the liberal position that individual empowerment is a good, but he acknowledges the collectivist concern that it is not necessarily an unqualified good.

He offers an enlightening look at the problems that can arise from putting "too much" power in the hands of the individual. Here he combines some of the findings of behavioral economics with real world policy issues to show the kinds of failures that humans can be prone to.

Most of these failures are familiar arguments in favor of paternalistic policies of doing what's best for people and "protecting them from themselves". Le Grand, rather than always moving to limit choice because of these possible failures, hopes to find instituional ways to limit their effect. For example, he discusses the value of moving sources of knowledge closer to the agents to help mitigate "irrational" choices made due to limited information. And he encourages building in stuctural incentives to guard against moral hazard and adverse selection effects.

That said, his argument for forced savings, i.e. that the future selves of the individuals need to be respected and given a voice, while novel, seems more like a justification than anything truly explanatory.

The final section contains several concrete proposals that attempt to apply his theories of motivation and agency to specific public goods. While most of his proposals are crafted for the UK, his arguments are general enough to be of interest to anyone concerned with modern welfare state policies.

While the proposals are too extensive to cover in detail here, they are worth mentioning in broad brush strokes to show where the theories take him.

In education, he advocates a form of school choice, like vouchers, pointing to their success in the UK. But he adds in what he calls a "positive discrimination" voucher that would encourage schools to counteract the stratification that is the most compelling argument against vouchers.

In healthcare, he obviously start from the British perspective of a National Health Service, but again argues for increased choice in providers to help harness market-forces for the sake of efficiency. He has a really interesting discussion of the kinds of incentives that manifested themselves (both for doctors and patients) in the various systems put in place by Thatcher and subsequently changed by Labour. He also highlights some of the specific problems associated with empowering people with regard to healthcare — particular the knowledge problem (i.e. the fact that not everyone has a medical degree and can make informed choices as consumers). He discusses the role of the GP in providing information and facilitating good choices by setting up systems that ensure that GP's incentives are balanced between helping their patients first and foremost, and furthering the public good in aggregate.

In social security, he argues for matching funds from the government to foster a sense of partnership in providing for retirement. A graduated scale where the first dollars saved were matched one-to-one, while later dollars were matched at lower rates would ensure that the rich did not get the lion's share. Again, he struggles again with the knowledge problem of empowerment and questions how the savings should be invested and by whom, and under what circumstances they could be used early (e.g. to buy a house or start a business).

His final proposal is the most bold and controversal — the idea of demogrants, cash given to citizens either at birth or at majority. He would fund this from increases in estate taxes. While libertarians should scream bloody murder at the coerced redistribution of wealth, the trade-off is the increased liberty in determining how the money is spent by pushing the decision making down to the individual. The main problem that I see is that society is unlikely to give the money without having some say in how it is spent, and this promises to be an ever increasing set of restrictions (the flip side of tax breaks). Second, for this to achieve the desired results, squandering the demogrant would need to have real consequences and lead to some hardships, or again, the incentives work against you – it's just a freebee. But any nation that decides to redistribute the money to everyone is also unlikely to make people face the full consequences of misuse.

In all, a great book, though I wished for more in some parts. It's greatest contribution is similar to that of Postrel's The Future and Its Enemies in that it provides a new and useful way to examine policies and proposals. As I watched the State of the Union speech tonight, I found myself thinking about whether each policy would make citizens queens or pawns, whether each program assumed that bureaucrats were knaves or knights. I hope this framework sticks with me throughout the 2004 election.

Bill Hobbs has a post about employment figures. The basic point is that the two methods of determing the employment rate: the payroll survey and the household survey are continuing to diverge. The bleak picture in the payroll survey, gathered from established companies, is not mirrored in the household survey, which captures the self-employed.

In fact, the payroll survey shows a net loss of about 750,000 jobs in 2002 (through Nov), while the household survey shows a net gain of close to 2 million.

I know several people who would not be counted in the payroll survey, but who are most definitely employed (in fact, one just complained about how well his business is going).

Check out the post, it has some interesting quotes from a Bear Stearns analysis [PDF], as well as a chart from a report of Congress' Joint Economic Committee.

Virginia Postrel has an article on Friedrich the Great at Boston.com. Reading The Constitution of Liberty was a pretty unique experience for me. I knew relatively little about Hayek at the time except "economist, libertarian economist" but I've rarely read anyone who just seemed so right so much of the time. He deserves recognition as "one of the most important thinkers you've barely heard of". His work on tacit knowledge and "the role of prices in coordinating dispersed information" is eye-opening.

Brad DeLong has some labor statistics that show how different this recovery from previous ones. But he says,

Kash of the Angry Bear reports that the decline in the labor force share over the past three years is concentrated among men, not women: it's not that the boom of the late 1990s and the associated extraordinary employment opportunities led women who in normal times would have preferred not to be in the labor force to find jobs, and that they are now returning to their normal out-of-the-labor-force state. That is not what is going on.

It seems plausible that, in this enlightened age, men with wives who still have good jobs might be the ones to decide to drop out of the labor force during the tougher times. Just because female employment grew during the boom times, it doesn't necessary follow that it would shrink during the downturn — families should rationally (barring stereotypes) have the less-employable member drop out of the market when they can't find a job — and today that just might be the man.

Brad DeLong calls the award of the John Bates Clark medal to Steven Levitt "a well deserved prize". Levitt was featured in a NYT magazine article this summer (Aug. 3) and is considered somewhat of a wunderkind in the economics world, known for his ability to approach difficult problems from a new direction.

His topics included the effect of school choice on educational results; the causes and consequences of distinctively black names; the effect of legalised abortion on crime; how to test theories of discrimination using evidence from the television programme, "The Weakest Link"; the gap in test results between blacks and whites in the first two years of schooling; gambling and the National Football League; and teachers who cheat in appraisals of their students' performance. Among the work he has published in prestigious peer-reviewed journals are a series of papers on crime and punishment, drug-gang finance, penalty kicks in soccer, money and elections, drunken driving, and the effect of ideology as opposed to voter preferences on the policies supported by politicians. In 2002 the impeccably sober American Economic Review published a paper co-written by Mr Levitt on corruption and sumo wrestling.

This NYT op-ed is an example of the kind of strange bedfellows that Virginia Postrel predicted in The Future and Its Enemies. A liberal Democrat and a conservative, supply-sider, together, holding dynamists at bay with their (separate) visions of (different) static futures. But they know what they're against....

Michael Kinsley offers balanced and insightful comments in Slate. (From Volokh Conspiracy).

An interesting puzzle at Professor Bainbridge about why Subways are franchises and Starbucks are corporately owned.

But more importantly, it's a cool example of how academic bloggers can latch onto an issue and write some pretty smart stuff about the topic, coming from multiple disciplines, in a matter of days. I can only assume that the future will simply bring much more of this dynamic, focused, but ephemeral collaboration. Interesting stuff....

I'm wondering about the different advertising models the two use, namely none for Starbucks and a lot for Subway. Is this a separate phenomenon, or tied to the same underlying structural features as the franchise/corporate question?

An excellent interview with Johan Norberg over at Reason: Poor Man's Hero.

Norberg is the author of In Defense of Global Capitalism and he gets so much of the globalization debate exactly right in this interview, from his criticism of anti-globalization groups, to his condemnation of Western textile and agricultural tariffs.

His path to these beliefs is equally interesting, starting with his "roots in the anarchist left" and his role in Swedish liquor liberalization.

Read the whole thing.

Some new posts on offshoring and outsourcing, which looks to be shaping up as a major issue in the 2004 election. First, Brad DeLong comments on an Economist article and wishes that they'd remember Say's Law, the interconnectedness of markets, and the lump of labor fallacy.

Dan Drezner links to a Institute for International Economics policy brief [PDF] on the globalization of the IT services industry. The brief tries to put the movement of jobs offshore in perspective given the "the business cycle, trend decline in manufacturing employment, dollar overvaluation, and technology bust".

Finally, you may have seen that Dell recently re-routed support calls for its corporate customers back to the US after customer complaints.

My current thinking is that, while certainly not a fad, the current pace of off-shoring will likely slow as some of the true costs are recognized. Like most major software and BPR investments, the benefits often look better on paper than reality and can be very hard to realize.

The key for policy makers will be to slow the shift just enough to keep the domestic political backlash under control, while being proactive with job training and unemployment insurance programs to help ease the transition. I also think a more liberal visa and immigration program (instead of the tightening in H1B's we've seen recently) could help the situation a bit, by helping American companies stay competitive while staying put.

Will Wilkinson is on to something here, I think. He discusses the idea of higher order public goods, upon the existence of which the provision of other public goods is predicated.

It's an important point — you can't just expect governments, or markets for that matter, to provide public goods like sewage systems, roads, health care, etc. without supporting norms and other internalized rules that make the provision of the other goods possible. Figuring out what those primary, necessary goods are is a challenge for those hoping to promote liberalism in the developing world.