Armed Liberal at Winds of Change points out a LA Times article about Kerry's thoughts on the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR):

Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kerry will announce a plan today in San Diego for reining in skyrocketing gas prices, saying President Bush has done nothing to stop increases that are hurting average Americans.Kerry's campaign said Monday night that the candidate would use a rally at UC San Diego this morning to propose increasing pressure on OPEC to produce more crude oil and to suggest that the United States should temporarily let supplies in its Strategic Petroleum Reserve be depleted, making more gasoline available for consumers.

I have to agree with AL's comments, "Truly, Deeply, Stupid":

So, let's see. At a time when our relations with the Arab states are as precarious as they have ever been, when Venezuela (another major source of imported oil) is in turmoil, and when domestic production is starting a long decline, Kerry wants to drain the SPI - the stock that exists to cushion shocks caused by cutoffs of imports (hence the name Strategic) so Soccer Mom and Soccer Dad can drive their H2 Hummers and Hemi Rams and not feel it in the pocketbook.

Meanwhile, I posted below an explanation about why gas prices are so high – contra Kerry, NIMBY sentiments about refineries and byzantine environmental regulations have more to do with it than Halliburton.

Update: Virginia Postrel links to her 1996 editorial in Reason about the "gas crisis" of the mid-nineties – still relevant today.

Slate has a truly excellent slideshow that is probably a more appropriate version of the plede of allegiance for today's young people.

Thanks to OxBlog for the pointer and the reminder about the Powerpoint Gettysburg address.

I'm in the process of trying to learn Arabic. Should you harbor any illusions otherwise, let me tell you that it is not easy. I'm finally pretty familiar with the alphabet and can read (or at least transliterate) and write very, very slowly. Surprisingly, the right-to-left thing is not as confusing as I thought it would be. On the other hand, the fact that it is an abjad, or writing system with consonants only, makes it very difficult to "sound out" words. Of course in beginner's books and in the Qur'an they do use vowels (marking the letters with little accent-like diacritical marks) but in most writing they don't.

One thing that is fascinating about Arabic is how you literally cannot learn the language without learning about the culture and Islam. Two side benefits: I finally understand why it's so hard to spell Qaddafi and I now know what some people's names mean. For instance, Kareem Abdul Jabbar means "generous servant of the Compeller" where Al-Jabbar (الجبر) is one of the many names for Allah.

It will all be pretty pointless until I get the CDs and learn how to pronounce it. For now, the letter ceyn just scares me because one book alternatively describes it as similar to gagging and "like a bleating lamb, but gentler". The explanation that it is a pharyngal voiced fricative didn't help either.

Oh, in case you're wondering (or your browser doesn't support it), the title of this post is the traditional Arabic greeting, "as-salaamu calaikum" or "peace be with you".

The whole system can be summed up by reaching in your neighbors' cookie jar with one hand while fisting yourself with the other, only less productive.

Peter Northrup of Crescat Sententia has a great post linking to several arguments for and against the French headscarf, or hijab (الحجاب), ban. Worth a read if you've though about the issue at all. He eventually argues pretty strongly against the ban:

there really is a problem in some French schools that involves the hijab. Unfortunately, this means that the law isn't just an illiberal overreaction to hysteria over increasing pluralism and immigration; it also leaves untouched a deep failure to protect a vulnerable community from serious harm.

These key "failure factors" are:An interesting read.

- Restrictions on the free flow of information.

- The subjugation of women.

- Inability to accept responsibility for individual or collective failure.

- The extended family or clan as the basic unit of social organization.

- Domination by a restrictive religion.

- A low valuation of education.

- Low prestige assigned to work.

In her New York Times column, Virginia Postrel points to some interesting studies about Getting the Most Out of the Nation's Teachers.

One study she cites, "Pulled Away or Pushed Out? Explaining the Decline of Teacher Aptitude in the United States" [PDF], attempts to explain why teacher aptitude, i.e. "teachers' propensity to be in the top achievement quartile" of academic aptitude, has fallen so much since 1960. The study examines two explanations: 1) that better opportunities and pay parity in other fields have siphoned off the best and brightest and 2) the compressed salary ranges due to increased unionization have led to equal pay regardless of merit, pushing the best out of teaching. The results? The compressed salaries can, surprisingly, explain 80% of the change in teacher aptitude (as measured by test score proxies).

While I obviously can't vouch for the econometric methodology, interesting results nonetheless.

The economist cited, Caroline Hoxby from Harvard, has a web page listing her other papers on education policy and funding, several of which are equally interesting.

Russell Roberts argues against a tax on fat. Specifically, he addresses the "externality" argument, the idea that because obesity is extremely expensive to the public health system, we should regulate it:

But if obesity causes health problems, doesn't that justify government's involvement? After all, if we taxpayers have to foot the bill for some of those higher health care costs, don't we have the right to intervene in each others lives?This argument has been used to justify the on-going and growing regulation of tobacco. It's actually a lie. Smoking causes people to die earlier and relatively quickly, saving enough in Social Security expenditures to overwhelm the health care outlays. That actually justifies subsidizing tobacco rather than taxing it if you think that we should base public policy based only on the impact on government spending.

I think that logic is grotesque. But it's more than grotesque. It's dangerous. AIDS is a very costly disease, and some of those costs are born by taxpayers. AIDS is associated with certain sexual practices. Does that justify government regulation in the bedroom?

I don't think so. But my eating habits or yours don't justify the government's involvement in the kitchen, either.

I was reading the New York Times Book Review article on Walter McDougall's Freedom Just Around the Corner this morning, and I came across this excerpt, quoting Samuel Huntington:

America is not a lie; it is a disappointment. But it can be a disappointment only because it is also a hope.I just think that's a great line.

Lynne Kiesling at Knowledge Problem, has an informative post on why gas prices are high and rising.

It's remarkable to me how little I knew about the pledge before the Newdow case. For instance, until the Ninth Circuit decision, I had no idea that the "under God" section was added in 1954, lobbied for by "the Knights of Columbus, to draw attention to the difference between God-fearing Americans and the godless Soviet Union", as Jack Balkin points out.

I also didn't know that the pledge was written in 1892 by Francis Bellamy, a Christian Socialist and devotee of his cousin Edward Bellamy's national socialist ideas. Edward Bellamy is famous for writing Looking Backward, a socialist "utopian" novel.

And finally, I didn't realize that the original salute to the flag that accompanied the recitation of the pledge was not the hand-over-the-heart that we see today, but instead was the one associated with the "Sig Heil!" of the National Socialist German Worker's Party. Alex Tabarrok is right, these pictures of children saluting the flag are creepy.

They don't teach these things in elementary schoool, do they?

Oh, supposedly Newdow did quite well arguing the case before the Supreme Court yesterday.

Gross ethical violation spotted at the Times.

From Reason, positive steps at the UN:

Imagine a better Washington. Imagine a conservative Republican administration working hand in glove with liberal congressional Democrats on a foreign-policy initiative designed to strengthen the United Nations while simultaneously increasing America's clout there. Imagine both parties and both branches bringing this initiative to fruition smoothly and unfussily, during an election year. Say, this year. Say, right now.Pinch yourself. It is happening.

Since 1996, a handful of foreign-policy wonks have been kicking around the idea of a "democracy caucus" at the U.N. Two administrations, first Bill Clinton's and then George W. Bush's, took quiet but significant steps in that direction. Now, according to Bush administration officials, the concept will be test-flown at the six-week meeting of the U.N. Commission on Human Rights that began on Monday in Geneva.

...

Late in the second Clinton administration, with a push from the State Department, the democracies began to organize. In 2000, 106 democracies gathered for the first meeting of an informal group they called the Community of Democracies. It had no permanent staff or formal powers, but it did produce an endorsement, in principle, of a democracy caucus at the U.N., a stance that the community reaffirmed in a second meeting in 2002 and, most recently, at a U.N. meeting last fall.

The Bush State Department then began lobbying Community of Democracy nations in a series of diplomatic lunches. "And these lunches with ambassadors from all different geographical regions—but all democracies—talked about all kinds of ideas, including this one," Paula J. Dobriansky, the undersecretary of State for global affairs, said in an interview. "Overall, it was very clear that other democratic countries from various regions embrace this idea and feel it could be of great value at the U.N., that it can bring together and highlight issues relevant to democracy."

All of that was groundwork. What had yet to happen was for the caucus to meet at the U.N. to do actual business: devise common positions, advance resolutions, eventually vote as a bloc on nominations and policies. It is this operational coordination that the administration hopes will now begin in Geneva, under the leadership of Chile, which currently heads the Community of Democracies' steering group.

In my mind, the UN has always had a two-pronged legitimacy problem. On the one hand, it is routinely ignored by everyone from North Korea, Iran, and Iraq to Israel, Russia, and the US, because of its relative impotence and unwillingness to truly deter. It has no credible threat to bring to bear.

On the other hand, it is ridiculed in Western states because autocratic regimes count as much as democratic ones, leading to such absurd situations as Libya chairing the Human Rights' Commission. To make matters worse, the veto-wielding states are frozen in a historical moment that is increasingly out of line with present facts. As the article points out, these realist compromises were necessary in the aftermath of WWII, when democracies made up a small minority of the nations in the world.

While not addressing the former, this new "democracy caucus" could help significantly with the latter. And as the article also points out, it should unite the Wilsonian idealists with the neo-conservatives currently in power.

This is obviously a big step because, at its core, it's a rethinking of the Westphalian order and a re-examination of the roots of sovereignty. Two hundred and fifty years after the Declaration of Independence, the world might be ready to embrace the fact that "Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed".

We (legitimately) forced Europe to roll back the tides of paleo-colonialism after WWII, reciting the mantra of self-determination. But we remained caught in the Continental framework of de facto sovereignty – a framework that legitimized autocratic and kleptocratic (but now home-grown) regimes. Needless to say the threat of global communism made this view convenient to the realists guiding our foreign policy during the Cold War, and they were more than willing to accept these ground rules.

But the post-Cold War order requires us to truly think through the question of sovereignty, statehood and war for the first time in 450 years. We must realize that these constructs are just that – constructed – and do not exist a priori. We recognize, and thus create and define, them through our actions.

Al Qaeda and "rogue" states challenge our current conceptions from different directions. Loosely affiliated terrorist networks that attack our homeland do not fit neatly into the bucket of "things against which you declare war", leading to confusion about whether the "War on Terror" is a marketing slogan or a state of affairs. Our popular view of what Al Qaeda is, is probably poorly informed by our understanding of how traditional, hierarchical states work – a fact born out, I think, by the difficulty in understanding the relationship between Al Qaeda, Ansar al-Islam, Abu Sayyaf, IMU, GSPC, Jemaah Islamiyyah, Silafi Jihad, etc. and the ongoing confusion about second-in-commands and senior leadership within the organization.

But despite the fact that we do not recognize them, and might not fully understand them, we must confront them.

"Rogue" and "failed" states challenge us from the other direction. We recognize them because they occupy territory, command armies, and make a claim of legitimacy. But our security and our humanity force us to question when it is justified to intervene – to remove an autocrat proliferating WMD or to stop a kleptocrat committing genocide. The problem is, when? And by whose authority?

The missed opportunities (Rwanda), partial successes (Serbia), and ongoing disagreements (Iraq) highlight the fact that a new order that answers these questions is yet to materialize. But the old order is being ushered out quickly.

There is obviously a huge gulf between the world today and the one envisioned in the Reason article, where democratic regimes control the taps of legitimacy. Much remains to be defined, and the view of this new order is just a rough sketch. But the Community of Democracies is an important step and offers hope that a new consensus can emerge – and one we might be proud of.

This, should it pan out, seems like very important progress: Iraqi Militias Near Accord To Disband:

Leaders of Iraq's two largest militias have provisionally agreed to dissolve their forces, according to senior U.S. and Iraqi officials. The move is a major boost to a U.S. campaign to prevent civil war by eliminating armed groups before sovereignty is handed over to an interim Iraqi government on June 30, the officials said.

Members of the two forces -- the Shiite Muslim Badr Organization and the Kurdish pesh merga -- will be offered a chance to work in Iraq's new security services or claim substantial retirement benefits as incentives to disarm and disband. Members of smaller militias will also be allowed to apply for positions with the new security services, but those that choose not to disband will be confronted and disarmed, by force if necessary, senior U.S. officials said.

Dan Drezner has an extensive article in Foreign Affairs magazine that is worth a read:

Critics charge that the information revolution (especially the Internet) has accelerated the decimation of U.S. manufacturing and facilitated the outsourcing of service-sector jobs once considered safe, from backroom call centers to high-level software programming. (This concern feeds into the suspicion that U.S. corporations are exploiting globalization to fatten profits at the expense of workers.) They are right that offshore outsourcing deserves attention and that some measures to assist affected workers are called for. But if their exaggerated alarmism succeeds in provoking protectionist responses from lawmakers, it will do far more harm than good, to the U.S. economy and to American workers.

A win for moderation: Malaysia's Islamic Party Loses Ground in Elections

The major Islamic party in Malaysia lost significant ground in parliamentary and state elections here today as the governing coalition of Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi coasted to victory.The Islamic party, Parti Islam SeMalaysia, lost the state legislatures in the oil rich northern state of Terengganu and in the neighboring state of Kalantan. In a humiliating loss, the leader of the party, Ulama Hadi Awang, lost his federal parliamentary seat.

The fortunes of the Islamic party, which won control of the Terengganu state legislature four years ago, were being closely watched as a barometer of militant Islam in Southeast Asia. Indonesia, the world's most populous Muslim country, holds parliamentary elections early next month.

The New York Times highlights the ripples in Syria:

Link via OxBlog.A year ago, it would have been inconceivable for a citizen of Syria, run by the Baath Party of President Bashar al-Assad, to make a documentary film with the working title, "Fifteen Reasons Why I Hate the Baath."

Yet watching the overthrow of Saddam Hussein across the border in Iraq prompted Omar Amiralay to do just that. "It gave me the courage to do it," he said.

"When you see one of the two Baath parties broken, collapsing, you can only hope that it will be the turn of the Syrian Baath next," he added, having just completed the film, eventually called "A Flood in Baath Country," for a European arts channel. "The myth of having to live under despots for eternity collapsed."

When the Bush administration toppled the Baghdad government, it announced that it wanted to establish a democratic, free-market Iraq that would prove a contagious model for the region. The bloodshed there makes that a distant prospect, yet the very act of humiliating the worst Arab tyrant spawned a sort of "what if" process in Syria and across the region.

...Syrians who oppose the government do so with some trepidation because it used ferocious violence in the past to silence any challenge. Yet the fall of Mr. Hussein changed something inside people.

"I think the image, the sense of terror, has evaporated," said Mr. Amiralay, the filmmaker.

For a while now, I've thought that the current capital gains tax system is completely messed up. This is based on personal experience of trying to manage my stock portfolio as well as theoretical thinking about what the tax code is trying to achieve.

The biggest problem, in my mind, with the current system is the "cliffs" that occur at 1 year (and previously occured at 5 years). Under the new rules for 2003 (actually just after May 5, 2003 which is it's own little nightmare for reporting) the rate for "short-term" gains (held under one year) is your normal income tax rate. The rate for "long-term" gains (held one year or longer) is 15% (for people above the 15% income tax bracket) or 5% (for people in the 15% tax bracket). The 2003 changes also repealed the "super-long-term" category for assets held over 5 years.

Now personally, this has always been a pain in the ass when it comes to selling stock because you have the situation (and this has happened to me several times) where holding on to the stock one or two weeks more will drastically lower your taxes, but it doesn't fit in to your investment strategy (e.g. you think the stock could drop in the near term) or your liquidity needs (e.g. you need the money to put a downpayment on a house).

Theoretically, I understand that the cliff is supposed to encourage long-term saving and discourage speculation. It's arguable whether these incentives need to be there – free-marketers would argue that they distort the market and limit healthy arbitrage. But, in a post-Enron world, there's more support for regulations that discourage quick profit-taking and encourage the long view. (And there actually are some findings from behavioral economics that humans have non-exponential discount functions and might need encouragement to be more "rational".) So, for the purposes of this post, I'll assume that the long-term incentive is desirable.

In light of these facts, I have a new proposal...

Instead of a "cliff" system, with multiple rates to add progressivity, we should move to one formula that provides a continuous tax function. My proposed function would be:

(gain on asset sale) * (marginal income tax rate) * 365

tax owed = ----------------------------------------------------------------

A * (days asset owned) + 365

Here the marginal income tax rate would be calculated based on your adjusted gross income as if the capital gains were included as regular income. This is the same method that is currently used to determine whether you fit in the 15% bracket or not. A is an accelerator that could be modified by law to determine how fast the rate decreased over time.

While it seems a bit more daunting, here are the advantages that I see:

Potentially, there could be options involved to ease the filings of lower income people. For instance, you should always have the option to just treat the gain as ordinary income, and perhaps there should be an income threshold or a perentage of capital gains to ordinary income under which you wouldn't need to file a Schedule D. In addition, tables could be provided that approximated the formula for people below certain income levels. But, particularly given the complexity of the 2003 return with the cut-off date, etc., this doesn't seem drastically more difficult than the current April 15 nightmare.

In general, I'm opposed to social engineering through the tax code – at least the income tax that goes into the general revenue account. Usually, externalities that the government is trying to internalize in the market should be handled through more targeted user fees, etc. But if we're going to have a system that progressively tax capital gains while encouraging long-term planning, this seems to make more sense to me than the current system.

Comments? Too complicated? Bad idea? Things I haven't thought about?

In Dallas, Child Tells Grandma Gorilla Tried To Eat His Head.

It's easy to lose track of other parts of the world with all of the focus on Iraq and أﻟﻘﺎﻋﺪﺓ all the time.

But Taiwan will be having elections on March 20. The contest is between Chen Shui-bian, the pro-indepence incumbent, and Lien Chan, the Nationalist Party challenger.

Chen won four years ago with only 39% of the vote, because the Nationalist Party was divided. It appears that he's had success in driving public sentiment towards a Taiwanese identity instead of a mainland one (see the statistics below).

Meanwhile, China is thought to be flexing it's military muscle on the eve of the election to intimidate the Taiwanese. This posturing has included joint military exercises with France off the coast of Taiwan just four days before the election (the largest ever with a foreign nation), as well as repeated missile tests since January . There is much speculation that the Chinese would attack the island if Chen wins again, largely because of his support for a referendum demanding that China remove its missiles pointed at Taiwan – a referendum seen as a precursor to an independence referendum.

Other than the fact that we've committed to protecting the democracy in Taiwan from mainland encroachment, this is relevant to the US because, by law, we are required to support the Taiwanese military through arms sales, and we have historically (though vaguely) asserted that we would help Taiwan defend itself in the face of Chinese agression. So this could get out of hand quickly.

USA Today provides a surprisingly good summary of the situation, including some interesting statistics:

44% — Percentage of Taiwanese who defined themselves as Chinese in September 1992 |

More: I had forgotten about this. But I wonder if the Sino-French excerises were motivated partially by the frigate bribery scandal from January:

Illegal payments linked to a French defense deal with Taiwan signed in 1991 have placed the French government at risk of being ordered to repay up to $600 million in murky commissions, according to a report published on Wednesday.

I really encourage everyone to go check out this Iraqi blog, Iraq the Model. It is usually very interesting and has lot's of details about the situation on the ground in Iraq.

It's particularly good right now, as Mohammed, one of the bloggers, is posting his diary entries from a year ago, right before the invasion began – one entry a day. His posts contain everything from the dinar-dollar exchange rate of the day, to the mood in the neighborhood, to his family's preparations for the war. It's really fascinating and I thankful that he kept the journal back then and is sharing it now.

Thought you'd all be interested (given our recent conversations) in the latest ACLU action message that I received:

From: Matt Howes, National Internet Organizer, ACLU

To: ACLU Action Network Members

Date: March 18, 2004Not satisfied with the new snooping powers granted by the PATRIOT Act,

the Department of Justice is now asking the Federal Communications

Commission to allow law enforcement the power to regulate the design of

Internet communications services to make them easy to wiretap.If implemented, the new request by Attorney General John Ashcroft would

dramatically increase the government’s surveillance powers and set a

precedent for opening the entire Internet to law enforcement. By

forcing technology companies to build “backdoors” in their systems for

wiretapping, the Ashcroft plan would also create weaknesses that

hackers and thieves could use to invade your privacy and steal personal

information like credit card numbers.The government already has more than enough power to spy on individuals

suspected of wrongdoing. This measure is the equivalent of requiring

all new homes be built with a peephole for law enforcement agents to

look through.Take Action! Tell the FCC and Congress that you oppose these new

wiretapping requirements.Click here for more information and to send a free fax to the FCC

Chairman and your Members of Congress:

Like many of the DOJ's post 9/11 requests, this is obviously opportunistic. Building in insecurity for the rest of us so they can have another tool to catch the bad guys (and notice how it can easily change from terrorists to any ol' bad guys) is plain stupid.

On the other hand, I don't know exactly what, specifically, Ashcroft asked for other than what the ACLU said (although based on history it is probably everything and the kitchen sink), so this may be somewhat overblown.

I mention below my fears that Al Qaeda would take the election results in Spain as a vindication of their strategy. There was skepticism in the comments about the motivations that led to the Madrid bombings.

Recently, online jihadist documents from a year ago have come to light that describe the strategy, and the intended domino effect. The New York Times reports:

For the last year the Israeli historian Reuven Paz has monitored jihadist writings about Spain, which focused on the Spanish government's participation in Iraq. "In order to force the Spanish government to withdraw from Iraq," one online tract read, "it is a must to exploit the coming general elections in Spain." It added that two to three attacks would ensure "the victory of the Socialist Party and the withdrawal of Spanish forces," the first domino in the collapse of the American-led coalition.

Researchers with the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment who have specialised in digging up original al-Qaeda releases and interviews, told the NRK television channel they had discovered a document on an Arabic website last year outlining al-Qaeda strategies on how to force the United States and its allies to leave Iraq, and pointing to Spain as the "weakest link"."It wasn't until yesterday when we were going through old material to find links to Spain that we understood what we were holding in our hands," project leader Brynjar Lia told NRK.

"We mainly had the impression that (the documents) referred to the situation in Iraq, but on closer examination we saw that they specifically refer to Spanish domestic politics and the elections," due on Sunday, he added.

According to the TV report, page 42 of the Arabic document reads: "We have to make use of the election to the maximum. The government at the most can cope with three attacks."

The document also reportedly predicts that the other partners in the US-led coalition would follow like "pieces of domino" if Spain were to withdraw from Iraq.

Bjørn Stærk discusses the same document, and has a translation of parts of the Norwegian report.

I have no idea about the authenticity of these documents or reports, but it certainly makes my fears more concrete.

Ratings of Specific Local Conditions |

|||

| Today | Compared to prewar | Expectations 1-yr. | |

| Good | Bad | Better | Worse | Same | Better | Worse | Same | |

| Schools | 72% | 26 | 47% | 9 | 41 | 74 | 3 | 14 |

| Household basics | 56 | 41 | 47 | 16 | 35 | 76 | 3 | 10 |

| Crime protection | 53 | 44 | 50 | 21 | 26 | 75 | 4 | 11 |

| Medical care | 51 | 47 | 44 | 16 | 38 | 75 | 3 | 12 |

| Clean water | 50 | 48 | 41 | 16 | 40 | 75 | 4 | 13 |

| Local gov't | 50 | 38 | 44 | 16 | 29 | 69 | 4 | 12 |

| Additional goods | 49 | 46 | 44 | 17 | 35 | 75 | 3 | 10 |

| Security | 49 | 50 | 54 | 26 | 18 | 74 | 5 | 10 |

| Electricity | 35 | 64 | 43 | 23 | 32 | 74 | 5 | 11 |

| Jobs | 26 | 69 | 39 | 25 | 31 | 73 | 4 | 11 |

More at the BBC.

I hope their optimism is rewarded.

More at the BBC.

I hope their optimism is rewarded.

Is it possible to point this out as being truly funny, without being branded a demogogue?

We'll see. I've grown sensitive enough to the accusation to think that I need a disclaimer. But hopefully, labelling it "Humor" will help people realize that I'm not trying to toe the Republican line, but just laughing at a clever use of eBay. (Via InstaPundit.)

First, Brad DeLong offers a more balanced view of the unemployment situation from Dana Milbank.

But for those of you who enjoyed all of the employment talk below, here's another graph from the BLS that goes to the heart of the matter:

This graph shows the number of unemployed and discouraged workers as a percentage of the labor force plus the discouraged workers. Discouraged workers are those who are no longer in the labor force because they were discouraged that they could not find a job. So this rate gives us a better indication of how many people would like to work, but can't (or couldn't) find a job.

Unfortunately, this data doesn't exist before 1994, so we can't get a more historical perspective on it. But it clearly shows that despite being significantly higher than the late nineties, this metric has moved significantly (in the right direction) since June 2003. The National Review would have done well to refer to this metric as well as the standard unemployment rate numbers.

While we're at it, here's another bit of under-reported good news. Average hourly wages of production, non-supervisory jobs (in constant 1982 dollars):

This should be the productivity gains kicking in, leading to higher average real wages even than during the bubble.

So I'm sticking to my not-all-doom-and-gloom position for now.

Two interesting articles about American Empire. The first, a review of recent books by Foreign Affairs (via Winds Of Change). It covers The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy and the End of the Republic by Chalmers Johnson, Colossus: The Price of America's Empire by Niall Ferguson, Fear's Empire: War, Terrorism, and Democracy by Benjamin R. Barber, Incoherent Empire by Michael Mann, and After the Empire: The Breakdown of the American Order by Emmanuel Todd.

No one disagrees that U.S. power is extraordinary. It is the character and logic of U.S. domination that is at issue in the debate over empire. The United States is not just a superpower pursuing its interest; it is a producer of world order. Over the decades -- with more support than resistance from other nations -- it has fashioned a distinctively open and rule-based international order. Its dynamic bundle of oversized capacities, interests, and ideals constitutes an "American project" with unprecedented global reach. For better or worse, other states must come to terms with or work around this protean order.Scholars often characterize international relations as the interaction of sovereign states in an anarchic world. In the classic Westphalian world order, states hold a monopoly on the use of force in their own territory while order at the international level is maintained through the diffusion of power among states. Today's unipolar world turns the Westphalian image on its head. The United States possesses a near-monopoly on the use of force internationally; on the domestic level, meanwhile, the institutions and behaviors of states are increasingly open to global -- that is, American -- scrutiny. Since September 11, the Bush administration's assertion of "contingent sovereignty" and the right of preemption have made this transformation abundantly clear. The rise of unipolarity and the simultaneous unbundling of state sovereignty is a new and volatile brew.

But is the resulting political formation an empire? And if so, will the American empire suffer the fate of great empires of the past: ravaging the world with its ambitions and excesses until overextension, miscalculation, and mounting opposition hasten its collapse?

I watched Chalmers Johnson talk about his book on C-SPAN a week or so ago, thinking (from the title) that it would be interesting. Unfortunately, he came across as more the Chomskian blame-America-first type, making it hard to get past the conspiracy theories about the military-petroleum complex to anything worth examining more closely. He spent most of the time arguing that the size of our military "footprint", or number of overseas bases, demonstrated beyond a shadow of a doubt our nefarious imperialist motives, for why else would you want so many bases. QED, empire. Not particularly compelling by itself. Foreign Affairs seemed equally unimpressed.

The second article is an essay by Phillip Bobbit in the Financial Times (I think that since I read this, they've put it behind their "members only" area. Porphyrogenitus hosts a mirror, though.)

Both are definitely worth a read.

Update: Porphyrogenitus has more comments on the Bobbit piece, here.

The coverage in the mainstream US press is pretty silent on this, but it's worth noting that Ba'athists and Kurds are clashing in northern Syria. More at the Free Arab Forum, via InstaPundit. Syrian forces have reportedly killed 250 people after a "football riot" turned into more than just that.

Also, a mini-rebellion has broken out in Fereydoon-Kenur, Norther Iran. The winning candidate from the recent elections (who won only after the Mullah's disqualified three ballot boxes) has resigned for fear of his life.

Whether these are encouraging events depend on whether you believe in the neo-conservative domino theory or are worried more about stability in the region. Regardless, I do wish they were given more coverage by the mainstream media. I suppose though that it is hard to get access to the facts in the kinds of regimes that we're talking about.

It is interesting to me that the unrest that has spread to other countries in the Middle East is from pro-democracy groups revolting against autocratic regimes, and not anti-American mobs as was predicted by anti-war groups prior to the war in Iraq.

I hope the people in both countries can achieve their objectives and shake up their oppressive regimes without too much bloodshed.

Update: More on the situation in Syria at Haaretz, including the report that a US team, including intelligence officers, have flown in to northern Syria from Iraq to help relieve tensions between the Syrians and local Kurdish leaders. President Bashar Assad sent his brother and Defense Minister to negotiate.

I don't want to get into the actual debate about Aznar/Rajoy v. Zapatero, whether Spain should be in Iraq, or how best to prosecute the war on terror.

But the election results today in Spain make me scared that Al Qaeda will try a similar action here in early November, to try to influence our election. And it is likely that Britain, Poland, Italy and/or Australia will see similar attacks, as Al Qaeda attempts to knock down the dominoes of American allies. They clearly wanted the Socialists to win in Spain, and whether true or not, they are sure to believe that their strategy was effective, and should be duplicated.

I'm afraid for the consequences....

I've been meaning to post about what I do for a living for a while now. Not because anyone has ever asked, of course, but because they really should and it hurts my feelings that they never do. Actually, that's not true, there's nothing worse than talking to someone and watching their eyes glaze over to the point that you'd like to dip your doughnut in their orbit.

But, here, safely ensconced far away from the glazing or the equally likely furtive glances searching for an escape route, I can write about my job to my hearts content.

But seriously, I'm actually working on some pretty cool stuff that I've wanted to post about for a while. Seriously.

The main research project that I've been working on for a while is on metamodeling and meta-metamodeling. While it can be used for mundane things of course, metamodeling is actually pretty cool. It captures a lot of the interesting parts about recursive and self-referential languages, as well as making you think about ontological frameworks.

So what is metamodeling (and its big brother meta-metamodeling)? Well, there are several relevant standards in this area, including the OMG's Meta-Object Facility (MOF), Unified Modeling Language (UML), and Common Warehouse Metamodel (CWM). But it's simplest to start off with a desciption of data and metadata. Everyone knows what data is (are). It's meaningful information, organized in some fashion, able to be retrieved. Perhaps stored in a database. But for now, let's think of the words of a book. Now everyone is also probably familiar with metadata, even if they are not familiar with that term. Metadata is data about data. So if the books are the data, then the card catalog that describes the books is the metadata. Each piece of metadata (each card in the catalog) describes a book, it's title, author, publisher, etc.

Now, for each card, a library might have multiple copies of the book (and certainly multiple copies exist in the world). Each of these copies is known as an instance of the metadata on the card. Now this is all well and good because we can all see how this is useful. I don't have to go look at the book to get some basic information about it, I can use the catalog and it can tell me if I care about the book or not. We'll just think hard about what information to put on the cards to make it useful.

So you might think that we can stop there. But it soon became obvious that the metadata on the cards was just more data and we might be in the position to want to describe what's on the cards. In fact, we may have two different card catalogs that have different information in them. So one might contain author, publish date, title and the other might have author, editor, page count, publisher. So, if I need to find books with the word "Piddle" in the title that are over 500 pages long, I need to know whether the card catalog has those fields in it before I make the trek to that library.

So now we can imagine a catalog of card catalogs that has a card for each library (and its card catalog), with each card listing the name of the card catalog, its location and the fields that are on its cards. Now we have meta-metadata. We could even get fancy and have a card in this meta-catalog, not for each card catalog, but for each type of card in a catalog. So we'd have a card that described what magazine cards looked like, and one that described books, one for anthologies, etc.

So you can see that we can keep doing this ad infinitum as necessary, and in fact, computer programmers talk about a meta stack. Here the levels are labelled M0 (data), M1 (metadata), M2 (meta-metadata), M3 (meta-meta-metadata).

To make things a bit more complicated, the meta- prefix is really relative, meaning that meta-metadata is both data (seen from its level, M2) and metadata about metadata (seen from the level M1), as well as meta-metadata (from M0).

Each object in a layer is considered an instance of an object in the layer above. Each book an instance of a card. Each card an instance of the meta-card that describes it.

To make things more confusing (but no more complicated), computer programmers sometimes use the word model to mean the same thing as metadata, so you might call the meta-metadata a metamodel instead. Sometimes (see UML above) they will also call a metamodel a modeling language since it describes models.

Now, it turns out that you don't need to actually build a stack that's infinitely high. In fact, most people stop at M3 – the meta-metamodel layer. And the reason for this is that they define the meta-metamodel in such a way that it defines metamodels. And then they define the meta-metamodel itself as an instance of itself, recursively. This is where it gets complicated, and you (at least I) start getting confused.

Anyway, more on this later....

Brad DeLong attacks Jerry Bowyer of the National Review for running fast-and-loose with the truth over the employment figures. Bowyer trumpets the fall in the unemployment rate from 6.3% in June 2003 (when Bush enacted his latest round of tax cuts) to 5.6% in Feb 2004. But Prof. DeLong has a problem with the argument:

Since June 2003, the household survey estimate of the number of working age Americans has grown by 1.53 million.* During that same period, the household survey estimate of employment has grown by 700 thousand. In order for the employment-to-population ratio to remain constant, a 1.53 million increase in the working-age population needs to be accompanied by an 950,000 increase in employment. According to the household survey, we are 250,000 short since last June at what we need to maintain the ratio of employed Americans to the working age population. For those extra 250,000 (according to the household survey), the past nine months' labor market news has not been good.

If you look at the February BLS report on employment you'll see what I mean. The Table A reports use the Household Survey data that he's talking about. The official numbers on the BLS site are slightly different than Professor DeLong's and I can only assume he's applying some sort of correction to try to account for the fact that the BLS adjusted their population estimates downward (and thus the household survey numbers) in January 2004 based on new census estimates.

A quick look at June 2003 shows a Population Level, Civilian noninstitutional population, 16 years and over of 221,014,000. Feb 2004 shows the same figure at 222,357,000 which my calculator tells me is only an increase of 1,343,000 people (not the 1.53 million he claims). Looking at the same months, I see the Seasonally Adjusted Employment Level go from 137,673,000 to 138,301,000 giving us an increase of 628,000 jobs (not the 700,000 he shows). Again, his numbers may have a fudge factor to back out the Jan nudge.

But, using his argument, to keep the employment-to-population ratio the same, you'd have to add (1,343,000 * 0.623) = 836,689 jobs. So there is a shortfall of about 209,000 jobs. This corresponds to a fall in the employment-to-population ratio of 62.3 to 62.2%. Now here's the part I have a problem with. Prof. DeLong tries to use this fall in employment-to-population ratio to say that all is doom and gloom and the National Review's optimism is misplaced:

So what has happened? What has happened is that, for a number of different reasons, a lot of people have given up looking for work. The fall in the unemployment rate is not because the number of jobs has grown to encompass a larger share of the adult population, but because the fraction of the adult population who are looking for work has fallen as people have dropped out of the labor force.

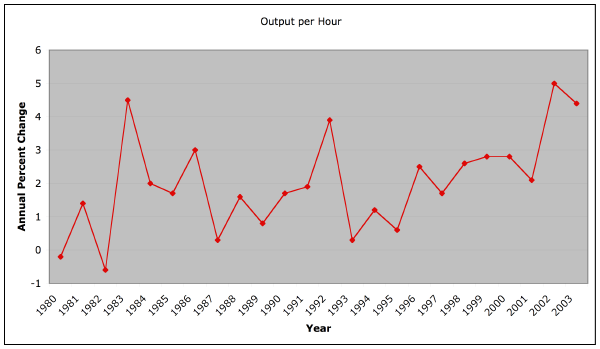

So why, oh why (to borrow a phrase from DeLong) would we want to compare ourselves to the dot.com bubble, about which there has been no end to the handwringing? That was unsustainable, that was why there was a crash. It makes complete sense that many people who wouldn't otherwise work decided to get a job in the biggest boom economy in 50 years. Comparing the present economic climate unfavorably to that one is foolish, and at best will simply encourage policies that lead to more bubbles. Here's another chart for you, of productivity growth:

Again, historically high levels. That's pretty damn hard to do. High labor participation rates, low unemployment, low inflation, high productivity growth. Not to mention during a war, just 2 years after the World Financial Center was turned to dust.

Now, everything is not perfect of course, and I think we probably do need to extend unemployment benefits because there's a great deal of transition going on in our economy now. But there is room for a little optimism, even from the National Review. The last thing we need is for a drastic change of policy because we're wishing for the good ol' unsustainable days of the bubble.

To put this in perspective from the other direction, just think, if we had the EU's average 8% unemployment rate, we would have another 3.3 million people unemployed.

So for the moment, we should be optimistic. Barring external forces, we seem to be in a pretty darn good recovery, and I think Alan Greenspan is right, even more jobs will follow soon. (2.6 million by year end? Nope. But a bunch.)

But external forces are what we should worry about. I argued below that the trade deficit will be handled by the floating exchange rate (that's what it's there for) but that oil prices were a big part of the rise. It's possible that continued high oil prices will put a break on the recovery – we should be concerned about that. It's obvious that Saudi Arabia is trying to influence our foreign policy by controlling the supply of oil, so we'll have to live with the higher prices until a) we back down from some of our democratic initiatives in the ME, b) we elect a new president that makes nice-nice with the Saudis, or c) the Saudis realize we won't give and decide they need the money to badly to keep prices high. Regardless of politics, I think c) is best for our national interest over all.

Update: I have an additional post with more graphs here.

Now this is a bit disturbing, and I'm sure that I'd be upset if I thought my body was going to be used as a cadaver at medical school and instead this happened: Bodies donated to [Tulane] medical school were sold to army for landmine tests.

But I wish they'd get the story right. Doesn't it sound at least a little more respectable that the bodies were blown up to test protective gear against landmines and not to test landmines. I don't know... to me that seems like an important distinction that the headline misses.

The Associated Press finds an interesting spin on the Iraqi spy case: Accused spy is cousin of Bush staffer.

Hmmm. Interesting. She worked for four Democratic members of Congress (including, most recently, one who ran for President) and several newspapers (including the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, which hosts the article) but the real story is that she's "a distant cousin of... Andrew Card".

These kinds of stories are what drive the right-wing nut jobs to scream "Slander!", etc. But you have to admit, it's pretty absurd reporting.

Update: Okay, it just gets worse. It turns out that Andrew Card actually turned her in:

The U.S. official was not identified. But federal sources told NBC’s Pete Williams that the official was Card, Lindauer’s second cousin. The sources said it was Card who alerted authorities to his relative’s activities. A government official, speaking on condition on anonymity, later told The Associated Press that Card was the recipient of the letter.

David Adesnik at OxBlog has more on the debate about John Kerry's flip-flops.

It's a rather calm description of a debate between two other (more polarized) bloggers, along with a slew of links. Worth a read if you care about this issue – and it does seem to be shaping up to be one of the main narratives of the campaign.

As Mike F. said in a comment, opponents do always try to label the candidate a flip-flopper. But my point is that it sticks on some and not others. We'll see if Kerry can successfuly change the topic.

One theory I've heard: once Bush starts attacking (which is sure to be nasty) he'll jump on the Kerry-as-waffler bandwagon, thus painting him into such a defensive corner that he'll be vulnerable and won't be able to distance himself in the final days from some of his more liberal positions.

The Associated Press paints a bleak picture for trade in January: Record Trade Deficit in January Fuels Political Fight:

America's trade deficit hit a record monthly high in January, the start of an election year in which Democrats hope to use the swollen trade gap and the loss of U.S. jobs as campaign issues against President Bush.The Commerce Department reported Wednesday that the trade imbalance mushroomed to $43.1 billion in the first month of 2004, representing a 0.9 percent increase from the previous month.

For all of 2003, the trade deficit posted an annual all-time high of $489.9 billion, according to revised figures.

So the rise in the trade deficit was $365 million and Democrats are going to paint this as a clear indication that Bush's trade policies don't work.

But reading to the end, and perusing the actual report [PDF] we see that exports of meat and poultry fell by $255 million in January due to mad cow disease. In addition, oil & gas imports jumped $768 million dollars (6.9%) in January, mostly due to a $2.08 (6.5%) increase in the price of oil from December.

So the "jump" doesn't look particularly terrifying, especially since the 3 month moving average for the trade balance is actually lower than it was in April and May of 2003.

Alan Greenspan is right – the weakening dollar will mostly fix this problem over time, as US exports get cheaper and foreign imports more expensive. This is already working, as imports from Western Europe fell $5.4 billion (41%) in January. The country with the largest imbalance was China, with whom our deficit grew $1.6 billion (16.2%). Since they peg the yuan to the dollar, we're not getting any benefit from the cheaper dollar and they seem to be taking up some of the slack from the EU. It remains to be seen how this will play out over the next 8 months as trade with China will be a big campaign issue. My theory? China will make concessions on the yuan, both to appease their US trading partners and to slow their 9.1% growth rate (which they've already hinted may be too fast to handle).

A bigger problem for us will be continued high oil prices, which could slow the recovery. OPEC doesn't seem to like Bush very much so we could be in store for continued high prices for a while. On the other hand, the Gulf States are so addicted to oil revenue that they'll have to raise production some time – i.e. it's likely they couldn't survive a prolonged shortage like in the 70's.

Anyway that's my take. Another prediction: it's going to be increasingly hard to sort these things out give all the rhetoric that will be sure to fly from both camps over the next 8 months. That's a bit scary since it would seem that "sure and steady" (rather than "frantic and reactionary") is the right policy in the near term in order to protect the fragile recovery.

Why am I worried about reactionary policies? We end with the following quote from US trade representative Robert Zoelleck before the Senate Finance Committee (via Drezner):

“With America’s high standard of living, we cannot successfully compete against foreign producers because of lower foreign wages and a lower cost of production.” Perhaps this pessimism sounds familiar. It could very well have come from one of today’s opponents of trade, arguing against a modern-day free trade agreement. But in fact these words were written by President Herbert Hoover in 1929, as he successfully urged Congress to pass the disastrous Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act that raised trade barriers, destroyed jobs, and deepened the Great Depression.

I seriously thought to myself, just for half a second, "hey, maybe he'll die..."

Ashcroft hospitalized with gallstone complications

But that's not nice no matter how awful you think he is. So let's just hope he's too sick to commit to another 4 years.

Update: He's still in intensive care. And with more thought, I feel even worse about my initial reaction. Here's to hoping he recovers fully, because I really don't wish any ill on him or his family – I just wish he wasn't Attorney General.

Last night I saw the new KFC commercial that tries to convince us that KFC stands for "Kitchen Fresh Chicken". It's the freshness that makes it good, not the fry!

In addition to the new slogan being difficult to say (which the commercial forthrightly admitted), the lawyers forced the advertising agency to flash the following disclaimer in very small letters that required judicious use of my TiVo to read:

Freshness guarantee does not apply to Hawaii or Alaska or during unusual supply situations.

Slate has an article on John Kerry's Waffles. It remarks, "If you don't like the Democratic nominee's views, just wait a week" and provides a handy table of his "evolved" views. Unfortunately, in almost every instance, I like the old Kerry more than the new.

Now that could just be the effect of the primary season, and he could move back to his "real" position in the general election, but let's just say that I don't like the trendline.

My post the other day praising Tom Friedman's op-ed on offshoring got a lot more criticism than I expected, both in the comments and verbally. Julia obviously laid into me in the comments. And Mike F. told me over brunch at his parent's house that in an area where we mostly agreed I picked the one quote that he thought was unsupportable. T McGee asked "what percentage of [my] posts involve... making an argument by anecdote?"

So it's worth reexamining the quote and trying to explain what I took away from it and why I didn't have the visceral negative reaction that others did.

First, it's worth saying again why free trade is supposed to be good. It all comes down to the fact that in the absence of tariffs, the increase in consumer surplus will be greater than the decrease in producer surplus. Combine this with David Ricardo's comparative advantage – trade is beneficial to both countries even if all goods can be produced more cheaply in one country than the other; it's the ratio of the costs of production that matters – and neoclassical economics argues pretty strongly for it.

The current politically hot argument against free trade is that it "destroys" American jobs – there are or have been other arguments, but in this election year, environmental and labor standard critiques are on the back burner compared to the effects on domestic workers. Listen to Kerry, Gephardt, Edwards or even Bush if you want to hear this argument (in fact, listen to anyone except Gregory Mankiw and Alan Greenspan).

But there are two ways that trade helps the country in the long run. The first is by offering lower prices, both for companies and consumers. This makes everything from food to durable goods cheaper for consumers. It also makes American companies more competitive in the global market by make their inputs cheaper (and hence their marginal costs lower). This is why steel tariffs and sugar quotas backfire – steel-using companies are hurt by higher prices and candy-makers move to other countries. People (including me) talk about this effect fairly often – it's the standard argument for free trade.

But the other effect is just as real, even if harder to see and longer in coming. The idea is that, due to rising standards of living over time, demand is created in other countries for American goods. Because of comparative advantage, we live pretty high up on the food chain of production – we have huge advantages in creative, marketing, high-tech and many other areas that require educated workers and efficient capital markets. That's good for us because it makes us highly productive and wealthy, but the problem is that it takes rich people to buy the stuff that we produce well. So it stands to reason that having more rich people to buy our luxury items, see our movies, use our software is good for us.

I took Friedman's op-ed to be an argument, not for shareholder democracy, we all benefit because investors do, but for this second benefit of free trade. It was an argument that was part anecdotal, part statistical, and part (implicitly) logical.

Exports to India have gone up 72% in the last 12 years. And these outsourcing companies are (anecdotally) buying our products to help get their businesses up and running. And this is an expected benefit of free trade.

That's what I thought was worth highlighting.

No, the components for the Compaq computers probably aren't built in the US, but the marketing, R&D, integration testing, financing, industrial design and (maybe) final assembly is. The Microsoft software probably is written here. What makes the Coke bottled water valuable (the brand) is mostly made here. And all the call center reps and computer programmers probably go home and listen to US music, watch Hollywood movies, and wear American brand clothes.

Anyway, that was my reason for pointing to the op-ed. Maybe I left too much unsaid, maybe I selected a bad quote, maybe you all still disagree with me.

As to T McGee's criticism, while the people I link to or quote often include anecdotes in their arguments, I think a perusal of my economics category (or the front page) will show more statistics and rational argument than anecdotes. I'd be interested in knowing what percentage (and which posts) he thinks are anecdote-based. I try to use real data and economic arguments as much as possible, but anecdotes can be illustrative and persuasive in a way that raw numbers and logic can't.

I posted below about the politics of science, not so much in defense of the Bush Administration as to call into question the objectivity of the Union of Concerned Scientists that issued the report.

I would be remiss if I didn't mention this recent example that seems to confirm the UoCS's concerns, at least about stacking advisory committees. It seems that Bush recently dismissed (registration required) two members of his council on bio-ethics:

President Bush yesterday dismissed two members of his handpicked Council on Bioethics -- a scientist and a moral philosopher who had been among the more outspoken advocates for research on human embryo cells.In their places he appointed three new members, including a doctor who has called for more religion in public life, a political scientist who has spoken out precisely against the research that the dismissed members supported, and another who has written about the immorality of abortion and the "threats of biotechnology."

The cynic in me still thinks this is probably the unfortunate SOP for presidents, but that doesn't mean we shouldn't criticize it.

Here's an interesting 1998 article on early Christian same-sex marriage in the Irish Times (although the link is to something called drizzle.com, I did confirm through a search, that the article does exist on the Irish Times site, albeit in a subscriber-protected area). Worth reading for anyone who opposes gay marriage for religious reasons. Here's a quote:

Contrary to myth, Christianity's concept of marriage has not been set in stone since the days of Christ, but has evolved both as a concept and as a ritual. Prof [of History at Yale, John] Boswell discovered that in addition to heterosexual marriage ceremonies in ancient church liturgical documents (and clearly separate from other types of non-marital blessings such as blessings of adopted children or land) were ceremonies called, among other titles, the "Office of Same Sex Union" (10th and 11th century Greek) or the "Order for Uniting Two Men" (11th and 12th century).These ceremonies had all the contemporary symbols of a marriage: a community gathered in church, a blessing of the couple before the altar, their right hands joined as at heterosexual marriages, the participation of a priest, the taking of the Eucharist, a wedding banquet afterwards. All of which are shown in contemporary drawings of the same sex union of Byzantine Emperor Basil I (867-886) and his companion John. Such homosexual unions also took place in Ireland in the late 12th/early 13th century, as the chronicler Gerald of Wales (Geraldus Cambrensis) has recorded.

Boswell's book, The Marriage of Likeness: Same Sex Unions in Pre- Modern Europe, lists in detail some same sex union ceremonies found in ancient church liturgical documents. One Greek 13th century "Order for Solemnisation of Same Sex Union" having invoked St Serge and St Bacchus, called on God to "vouchsafe unto these thy servants [N and N] grace to love one another and to abide unhated and not a cause of scandal all the days of their lives, with the help of the Holy Mother of God and all thy saints." The ceremony concludes: "And they shall kiss the Holy Gospel and each other, and it shall be concluded."

My take away: even if these ceremonies aren't strictly speaking "gay marriage", they do call into question the assertion that marriage as the union of a man and woman only has been an unchanging pillar of Christian society – it seems much more likely that various unions with various social meanings have been performed and celebrated within the Chuch since the early days. The meaning of love, commitment, kinship, and parenthood are continuing to change as the world around us changes and so should our institutions.

So it looks like NASA is about to make a big announcement about water on Mars. I'm watching the live feed of NASA TV on the internet. More later...